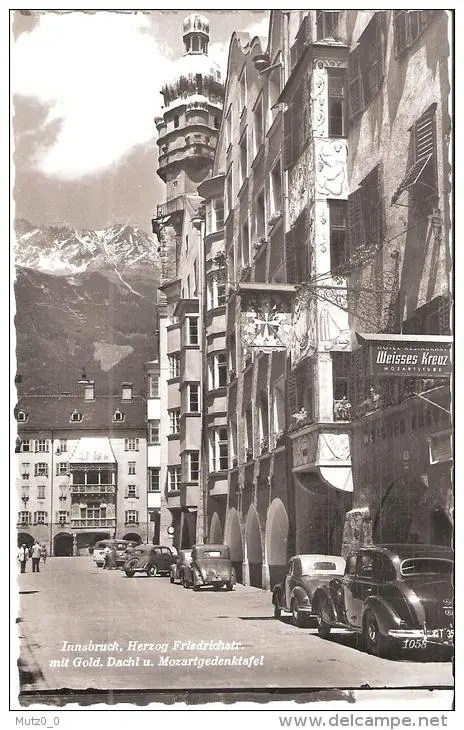

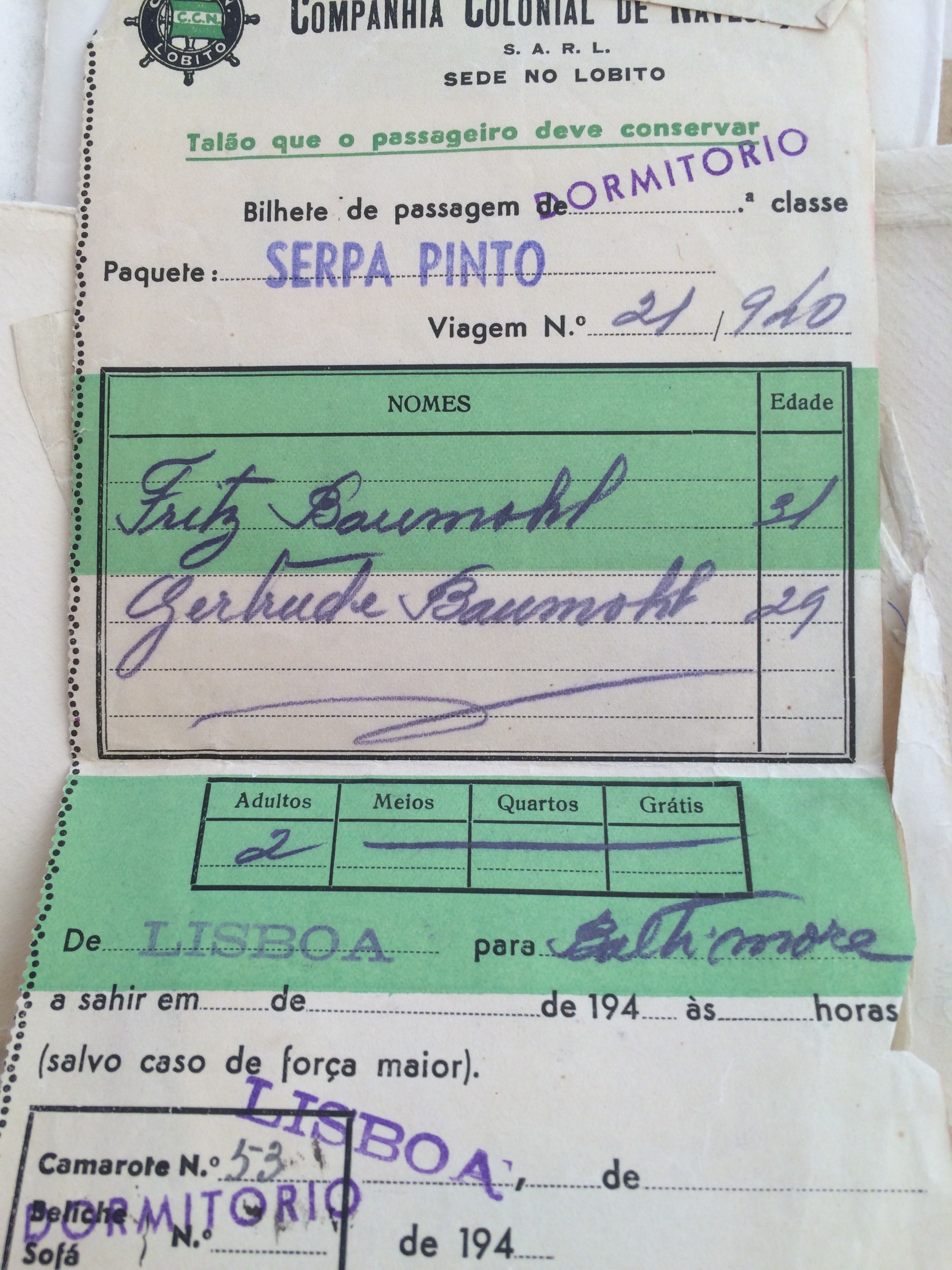

Currently, my characters Gisi and Max are traveling by train from Innsbruck to Venice over the Brenner Pass. In Venice, they’ll spend a couple nights in a youth hostel. It’s a much-needed short vacation for them, and a chance to try out Leo and Hugo’s recently forged Ausweis, or exit permit.

This is how may current writing process works. Once I’ve decided on a general framework for the next section I’m going to write, I do the research. I look at the history of the time and place in as close detail as I can—the Internet, for all its failings, is the most unbelievable library—as well as in the big picture. I fill pages and pages with cut and pasted images and text.

The archives of the New York Times are very useful, and I follow parallel stories in fiction and memoirs, and movies. I listen to music from the era. Currently, I reading Irene Wittig’s All that Lingers, which is set in the same time and place as Underground. The research for the particular section I’m writing now is taking me longer than usual because the characters are traveling to some places I’ve never been to.

When I’m feeling like I’ve done enough research, I start to imagine what my characters might do in the setting. Gisi and Max pass through Innsbruck on their way to Venice, so Gisi could see her cousin who lives there. The cousin’s husband is a Nazi; that could make for an interesting conversation. Maybe I’ll have Gisi and Max change trains in Innsbruck and give them a three hour wait, enough time to have meal with the cousins. Would Max be willing to do that?

Here’s how the piece I’ve written about that begins:

Chapter 21

Innsbruck

Vienna

September 2, 1936

When Gisi sees that other than by taking the night train, which would mean missing the views, the least expensive tickets she and Max can get to go to Venice includes a three-hour layover in Innsbruck. She suggests to Max that she write to her cousin Litzi to arrange to have lunch with her and her husband, Horst, who live there.

“I know he’s a Nazi,” she tells Max, “but I grew up with Litzi and I don’t want to lose her entirely. Surely we can steer the conversation away from hot topics.”

“You think so? Gisi, he hates me. He doesn’t even know me but he hates me. Why should I share a table with him?”

“Because you claim to be a pacifist? Because it takes two to tango?”

“I’m not sure I want to subject myself to that. I’m not sure I’m capable of it. I’m not Jesus Christ, Gisi.”

“He was perfectly well-mannered when I met him at Christmas a few years ago.”

“When he was pretending not to be a Nazi. Things have changed. He has no reason not to show his true colors now.”

“Then do it for me. If it gets ugly, we’ll stand up and leave.”

“Why don’t you and Litzi meet and I’ll spend the three hours in a bookstore or a cafe?”

“Maybe. But let me write and see what Litzi thinks. Then you can decide.”

Innsbruck

September 4, 1936

Litzi stands by the open window reading Gisi’s letter.

“Horst?” she calls into the hall. Her husband, returning from work with the daily paper tucked under his arm, hangs up his hat and comes into the sun-filled living room.

“My dear? You had a good day?”

“Yes, naturally. The boys haven’t come home yet, though, and I wanted to discuss this letter I received from Gisi today with you.”

Horst pats his thick blond hair into place and makes himself comfortable on the divan. “Alright,” he says. “What is it?”

“First, Gisi asks me not to discuss this with you, but how can I not? You’re my husband. I have to. But if what she is suggesting does come about, I would ask you not to let her know that we talked about her proposal so soon. You’re willing to do that?”

“Of course. What is she proposing?”

“Well, she and her friend Max will be in Innsbruck for a few hours on a stop between trains. They’re going to Venice for some reason. Since they’ll be here from eleven to two thirty, she suggests we have lunch together at a restaurant near the train station.”

“With Max? That sleazy Jew?”

“With Max. Though she says he isn’t eager to do it. He says he would rather wait at the station while she and I meet alone.”

“That sounds reasonable to me. Why not do that? I have no desire to share a table with a Jew, and a Socialist Jew at that.”

“I know he’s a Socialist Jew,” she tells Horst, “but I grew up with Gisi and I don’t want to lose her entirely. Surely we can steer the conversation away from hot topics.”

“You think so? Litzi, he hates me. He doesn’t even know me but he hates me. Why should I spend time with him?”

“Because you claim to be a Christian? Love your enemies? Blessed be the Peacemakers?”

“I’m not sure I’m capable of it. I’m not Jesus Christ, Litzi.”

“Then do it for me. If it gets ugly, we’ll stand up and leave.”

“Maybe. I’ll think about it.”