Questions have been coming up at my book talks and interviews about the origins of the philosophy behind the utopian vision that is now called Red Vienna, which is also the title of the first volume of Two Suitcases. This article from Jacobin Magazine is the best one on the subject that I’ve come across:

Two Suitcases

Unveiling Red Vienna at the UU and a Radio Interview

I spent most of last week among dear old friends, introducing Red Vienna to them through a book talk at the UU, home of free thinkers, activists, and a good number of eternal optimists, and a talk radio interview with Dave Congalton, grand master of the genre and a true mensch.

You can listen to the interview here: https://www.920kvec.com/episode/hometown-radio-06-20-24-430p-eve-neuhaus-author-of-red-vienna/

Now, back to baby and toddler duty. What a joy to be California with my family!

Red Vienna: this week’s events

I’m getting excited about this week’s radio interview and book talk. Join me if you can.

The radio interview will be on Dave Congalton’s show on KVEC on Thursday, June 20, at 4:30m in the afternoon. If you can’t listen live, it’ll be posted here: https://www.920kvec.com/show/dave-congalton-hometown-radio/

The following day, I’ll be sharing my book and and answering questions at the SLO UU from 4 – 6 pm.

Two conversations

Here’s the chapter of Underground that I just finished. Gisi and Max are planning to write a second article with information coded in it about the safest routes for refugees to take to leave Austria if it’s necessary. It’s 1937, less than a year before the Germans will annex Austria.

Two Conversations

April 16, 1937

a cafe near Max’s shop

A couple weeks later, on that first balmy day of the year when everything blooms at once and the air is full of rich fragrance, Gisi is rushing down the city street on her way to meet Max. When she arrives at the cafe near Max’s workshop the outdoor tables are already filling with spring revelers. It had been a long, hard winter for so many, in so many ways.

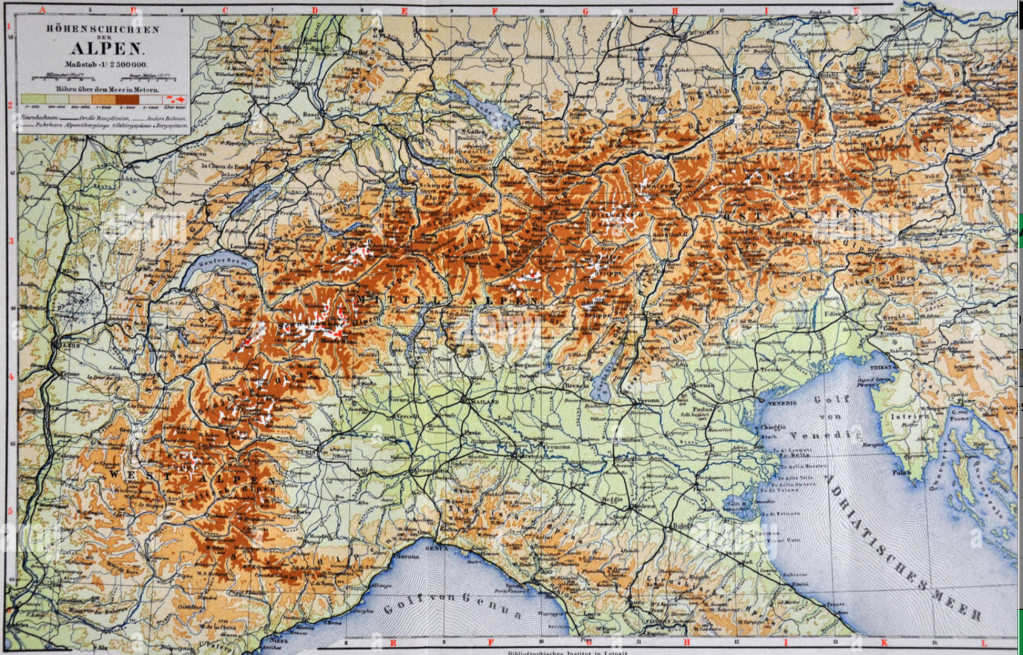

Gisi chooses an indoor table in a private corner, sits so she can watch the door, and pulls out a map from her bag. She unfolds it carefully and lays it flat on the table. Thoughtfully, she runs her finger along the routes from Austria to Italy that she and Max are considering. All of them are longer than the one they’d chosen for their first newspaper story. Even the shortest would require at least two overnight stays.

She has mixed feelings about going. Not only would all the proposed hikes take longer and require more preparation, but the story would take longer to tell and the article longer to write. And, it would take up more space in the newspaper, making it harder to sell. She sighs.

At the only other occupied table in the room, a couple in their forties is arguing. Though they’re trying to be quiet, Gisi can’t help hearing the woman’s adamant responses to her companion’s softer words.

“Don’t be a fool,” snaps the woman. “Mussolini will say whatever he wants Schuschnigg to hear.” A pause follows. “Of course he’s in league with Hitler! Why shouldn’t he be?” The pitch of her voice is rising. “Mussolini, Hitler, Franco, all the Fascists, they have nothing to lose by banding together.” Another pause. “Only we, the Jews, the immigrants, the travellers, the dark-skinned ones, all of us who are different, have something to lose!” A longer pause. Then she almost hisses, “But we have the money to get out, Fredl! And we have somewhere to go!” She listens for a moment and then says, “I don’t care if you don’t like my sister. It doesn’t matter. She’s offering to help us.” Another long pause.” And whose family has the means to do it? Yours?” She snorts.

Now Gisi can hear the man’s voice too. They’ve forgotten she’s there.

“It’s not a matter of the money, Lotte,” he says, slumping forward, elbows on the table. “You know that. You know it too well. But how can I leave my family, Lotte? What will happen to them?”

“You have a brother.”

“Yes, and you have a sister. Your sister has some good qualities and some less good ones—like my brother. No, I can’t leave. My life is built around caring for my family, and we’re rooted here. My life is in this city, in this country, no matter who is in power.”

“And my life isn’t here? You think I’m not leaving anything behind by emigrating? The issue isn’t what we have here now, Fredl. It’s what we won’t have when Germany takes over.” From the corner of her eye, Gisi sees the woman raising her hand to stop her husband from speaking. “Don’t talk about me how assimilated your family is. My cousin tells me how it is in Germany now. Jews have no rights. It doesn’t matter what kind of a Jew you are, rich or poor, practicing or not, we’re treated more and more like animals there. It’ll be the same here. Soon. Face it, Fredl. Is that what you want?”

“No. No, of course not.” He sits up and takes a sip of his coffee. “But we Viennese would never treat Jews the way the Germans have.” He puts down his cup. “We’re civilized here.” Even from across the room, Gisi can hear the doubt in his words. She realizes she hasn’t believed that for many years.

At that moment, Max enters the cafe bringing with him a rush of fresh air. He smiles at Gisi, who’s studying the map with a serious expression on her face. She looks up and smiles back at him, but the other couple’s argument is disturbing her, and her smile doesn’t reach her eyes.

He slips his jacket onto the back of the chair. “Well? Have you decided on which of the hikes we should take?”

“Oh, Max, I don’t know. Sit down and we’ll talk about them, but I have to tell you right away, I’m not sure I want to go on any of them.”

Max deflates as he sinks into his chair. “None of these particular hikes or none at all? Why not?” He can’t hide his disappointment. “I was so looking forward to it.”

Gisi lays out all her reasons: the time, the expense, the length of the article. It’s a strong argument and she becomes more convinced of it as she talks.

“So that’s it? Your mind is made up?” He stands up and begins to put on his jacket.

She relents. “I said we’d talk about the routes. You can still try to talk me into it. I just wanted you to know how I feel about it now.”

Max sits down again. “You’ve studied them? What did you find?”

“I read whatever I could find, and I talked to people. We were right about the routes we’ve been considering, but there are more. Smugglers have been using these trails for centuries. Now they’re in the business of smuggling people.”

“That makes sense,” he says. “It’s not too hard to find a smuggler to get you to Brno.”

“Although they’re not always reliable, as Hugo discovered.”

“You never know what to expect of people you meet along the way. I heard a story about a guy hiking and skiing into Switzerland who was picked up by some Heimwehr soldiers. It turned out they were more interested in what was in his rucksack than in turning him over to the authorities. Anyway, Switzerland was a kilometer away and it was many kilometers to their headquarters, so they escorted him to the border and left him there. Unfortunately, they’d robbed him, so he had nothing to show at the border, and guards turned him away. He walked back the three days it had taken him to get that far—without money, papers, skis, or even a winter coat.” Max shakes his head. “Poor guy.”

“At least he survived,” Gisi says.

“That’s true. People trying to escape from Germany wouldn’t be so lucky.”

Gisi looks down at the map. She doesn’t want to think about the horrors people are facing. “There at least a dozen well-used routes,” she says. “The shortest is the one we already tried, from Innsbruck to the Brenner Pass. Next is this one.” She points to the map. “You take the bus from Innsbruck to Naubers, which is a ski resort where strangers don’t stand out, and then it’s two and a half hours on foot to the border at Reschen Pass. It’s a much more rigorous hike than the one we took, but not as long or dangerous as most of the high mountain routes. I didn’t even study those. There are also, even at the very high altitudes, a handful of mostly flat routes that run along rivers, but they would take a very long time, days and days, even a week or more.”

“So the only reasonable one for us to explore is over the Reschen Pass. And we can do that! It’s only two and a half hours, you said?” Max is pleased.

“But they say some parts of the walk are challenging if you don’t have a head for heights. Do you have a head for heights?”

“Well…”

“And we’d need mountaineering equipment, trekking poles, warm, light-weight jackets, and better boots than either of us have.”

“Surely we can borrow what we need. Everyone in our circle supports this project.” He isn’t ready to give up.

She goes on, “It would be expensive, too. In addition to the train to Innsbruck, we’d have to pay for the bus to Naubers. Figuring out which of the hostel and restaurant owners would be willing to help refugees means we’d have to sleep and eat there, at least at some of them.”

Max has no response to that. “I don’t understand why you’re so negative about the project all of a sudden. Last time we talked about it you were all in favor. What happened?”

Gisi thinks. “I guess when I went into it more deeply, it didn’t seem so easy.”

“Nothing you’ve said has convinced me that it’s impossible though. Train, bus, and a two and a half hour trek—what’s so hard about that?”

“It’s everything together, but mostly, I find it frightening to imagine the two of us edging slowly along narrow path on a cliff with a thousand meter drop-off below us.”

“Come on, Gisi! You’ve skied so many times!”

“This is different.”

“It’s not. And everything else, we can manage easily.”

“No, Max. It would be much longer than our last trip—six hours on the train to Innsbruck and three more to Naubers, at least one night in Naubers, another six hours round-trip on foot to the border, and another night in Naubers, and then a full day to get home. And that doesn’t include all the time it’ll take to talk to people in order to write the article. Or the time it’ll take to write the article. It’s just too much.”

“So you’re giving up? You’re not interested in our project anymore?”

She sighs. “I just think it’s too much.”

He doesn’t argue. Instead, he takes his jacket and walks out the door.

At the other table, the couple who’d been arguing earlier have stopped. The wife is staring at her husband stonily as he slowly finishes his pastry.

Outdoors, clouds cover the sun and a cold wind cuts across the cafe. People are putting on their sweaters and coats.

This is how is it’s done

From the New York Times, March 14, 1938:

While researching the annexation of Austria by Germany, I came across this speech given by British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain to the Parliament the day after it happened.

In brief, Chamberlain says that on February 12, 1938, the Austrian and German Chancellors met and agreed on an extension of the framework set up by an earlier treaty. That treaty “provided, among other things, for the recognition of the independence of Austria by Germany and the recognition by Austria of the fact that she was a German State.”

The following week, Austrian Chancellor Schuschnigg “decided that the best way to put an end to the uncertainties of the internal situation in his country was to hold a plebiscite under which the people could decide the future of their country.”

On March 11, two Austrian Nazi members of the Austrian Parliament “presented an ultimatum to the Chancellor. They demanded the abandonment of the plebiscite and threatened that if this was refused, the Nazis would abstain from voting and could not be restrained from causing serious disturbances during the poll.”

“Later that day, feeling himself to be under threat of civil war and a possible military invasion, the Chancellor gave way to the two Ministers and agreed to cancel the plebiscite on condition that the tranquillity of the country was not disturbed by the Nazis.”

That’s how it was done. It’s probably why the far right and its leadership is getting away with so much in the US now.

Text of original speech:

FOREIGN AFFAIRS (AUSTRIA).

HC Deb 14 March 1938 vol 333 cc45-169

3.37 p.m.

The Prime Minister (Mr. Chamberlain) The main sequence of events of the last few days will be familiar to hon. Members, but no doubt the House will desire that I should make a statement on the subject. The result of the meeting at Berchtesgaden on 12th February between the German and Austrian Chancellors was stated by the former to be an extension of the framework of the July, 1936, Agreement. Hon. and right hon. Gentlemen will recollect that that Agreement provided, among other things, for the recognition of the independence of Austria by Germany and the recognition by Austria of the fact that she was a German State. Therefore, whatever the results of the Berchtesgaden meeting were, it is clear that the agreement reached was on the basis of the independence of Austria.

On Wednesday of last week Herr von Schuschnigg decided that the best way to put an end to the uncertainties of the internal situation in his country was to hold a plebiscite under which the people could decide the future of their country. Provision for that plebiscite is made in the Austrian Constitution of 1934. This decision on the part of the Austrian Chancellor was unwelcome to the German Government, as it was also unwelcome to the Austrian National Socialists themselves. Matters appear to have come to a head on the morning of 11th March when Herr von Seyss-Inquart, who had been appointed Minister of the Interior as a result of the Berchtesgaden meeting, together with his colleague Dr. Glaise-Horstenau presented an ultimatum to the Chancellor. They demanded the abandonment of the plebiscite and threatened that if this was refused, the Nazis would abstain from voting and could not be restrained from causing serious disturbances during the poll. The two Ministers also demanded changes in the provincial Governments and other bodies. They required, so I am informed, an answer from the Chancellor, before 1 o’clock in the afternoon. The Chancellor declined to accept this ultimatum, but offered a compromise under which a second plebiscite should be held later, with regular voting lists. In the meantime, he said, he would be prepared to make it clear that voters might vote for his policy but against him personally, in order to prove that the plebiscite was not a personal question of his remaining in office. Later that day, feeling himself to be under threat of civil war and a possible military invasion, the Chancellor gave way to the two Ministers and agreed to cancel the plebiscite on condition that the tranquillity of the country was not disturbed by the Nazis.

The Real Edith Tudor-Hart

In the part of Underground I wrote today, it’s April 4, 1937. Austria has had a Fascist government for several years, anti-Semitism is rising rapidly, and the possibility of Germany taking over Austria is becoming very real.

As they walk along a path in the Vienna Woods, Anna confides in Gisi that she recently wrote to their old acquaintance, Edith Suschitzky, now Edith Tudor-Hart. Anna is hoping that Edith can help her find an Englishman to marry, as Edith had found Alexander. For Anna it would be solely a marriage of convenience— it would get her a visa.

Edith is a secondary character in Red Vienna. She’s one of the real people scattered throughout the narrative. I have no idea if my parents, on whose story the books are based, ever knew the real Edith Suschitzky, though they may have. She was living—and taking the photographs described in the book— in Vienna at the time that I wrote her into my story. Her father did own the Social Democratic bookstore, her brother Wolf is real. It’s true that Edith married Alexander Tudor-Hart, that she was arrested, and that they moved to England.

Today, while checking the spelling of her name, I came across a documentary about Edith Tudor-Hart that hadn’t been released when I did the research for Red Vienna. It’s called Tracking Edith, and it’s available on Vimeo.

Wow. I knew I wanted to include Edith in my book the first time I read about her, and I knew much of what’s in the film, but there’s so much more. There are things I wish I’d known when I wrote about her, and things that I got wrong. And by no means have I told Edith’s whole story, just a tiny bit of what could have happened. Much of the really juicy part of her life hadn’t happened yet, or it was happening then, but there’s no way my characters could have known about it. I don’t want to spoil Red Vienna for those of you who haven’t read it, so all I’ll say here is that Edith’s story is probably the biggest of any of the characters in my books.

Do look her up, and watch the video. And read Red Vienna, too.

Just when you’re not expecting it…

Three days ago a friend suggested I join a Facebook group I’d never heard of, the Dull Women’s Club, so I could read some of the wonderful stories ordinary women from all over the world have posted. After about half an hour of reading, I dashed off an introduction to myself and my quiet world here in rural France. Who knew that a couple days later that post would have so many likes (12.5k this morning) and that it would lead to having contact with so many remarkable women? What an incredible experience.

I spent most of the next two days responding to the comments. I wanted to respond to every single one—so many of them touched my heart so deeply. What’s amazing about the stories is their ordinariness.

My teacher Alice O. Howell‘s book The Dove in the Stone is subtitled Finding the Sacred in the Commonplace, and that’s been my path ever since I first read it. I even facilitated a long-running discussion group about the book at my dining room table on Thursday mornings. But even though I was exploring the book every week and had a reasonable understanding of it, I can remember the exact moment that its importance sank into my bones.

We had a huge house in California then, very different from the little one we live in now. One or two of our five kids were always in college then, causing a major drain on our finances, so I cleaned the house myself. One day I’d climbed up to dust a high shelf and I was thinking about how to present the next chapter in The Dove and the Stone the next day. I picked up a small vase and was turning it in my hand to get the dust out of the cracks when it struck me.

Our big house

The understanding hit me in the heart like an electric shock and then rippled through my body. This is it. This is what I’m here for, to see the sacred in the commonplace. I had to climb down and make a cup of tea.

Our little house in France

So, when I came across the Facebook group filled with introductions to ordinary women my heart filled with joy. For the second time in my life I felt that I’d truly met my tribe. (The first was when I was 12 and went to an art and music camp for the first time.) But this time the tribe is hundreds of thousands of women.

Suddenly, as a result of the opportunity of meeting so many people through the facebook group, Red Vienna, is selling well, and lots of people are reading my blog.

On top of that, I found an outstanding narrator to for the audiobook version and her first sample arrived in my mailbox this morning.

I cannot express my gratitude. It’s over the top.

Another relevant excerpt: Hitler’s speech

This one is from the second volume of Two Suitcases, which is called Underground. If you haven’t read the first volume Red Vienna yet, order it at your local bookstore or through Amazon.

February 2, 1937

a cafe not far from Max’s workshop

Gisi turns the pages of the new issue of the Kronen Zeitung she spread on the cafe table. She’d seen several copies on her way to the cafe. The paper’s populist touch allowed it to survive the Fascist takeover of Austria and keeps it on the newsstands in working class neighborhoods.

On the second to the last page, she finds what she’s looking for: From Innsbruck to Italy—Three Winter Hikes, by Wilhelm der Wandersmann. It’s Max’s and her first effort at hiding coded information about safe escape routes in the paper. She’s pleased to see it, of course, and she feels confident that no one who doesn’t know the code could possibly suspect anything, but it bothers her to think about the lies she had to tell to get it published .

The son of the publisher, a sweet but naive young man, now waits for her after lecture every week, or worse, he arrives early and saves her a good seat. Gisi puts on her spectacles to discourage him, but it hasn’t worked. She can’t tell him about Max so she told him that she’s helping a cousin in Tyrol to get a start in journalism instead.

“My cousin is more of an outdoorsman than a writer,” she’d said to him, “but he wants to write a series of articles like this about hikes all over the country. He’d like to make his love of hiking pay for itself. That’s why he’s using a catchy byline instead of his own name.”

What she feels worst about is that the day she gave the publisher’s son the article, she let him take her out for coffee and a pastry. Encouraging him even that much is so wrong.

Max rushes into the smoky cafe. “Sorry I’m late,” he says breathlessly. “I sold another radio and had to pack it up. I only have two left now.” They kiss lightly. “So, let’s have a look at our man Wilhelm der Wandersmann’s article!”

The code isn’t complicated. It involves starting certain sentences with letters that indicate the political bent of the proprietors of inns and restaurants along the way. Each time Gisi and Max succeed in publishing another article, a new code will be shared, again in code, in the Arbeiter Zeitung.

“It’s fantastic!” he says, smiling broadly. “I can’t wait to take the next hike with you.” The next hike will be considerably longer with at least two overnight stays, quite possibly three.

Their conversation turns to how much fun they had hiking the trails for the article over the last six months, two of them more than once. In the end, they decided that only one of the three routes would be safe, and they’d written the article together, he injecting the humor into her fastidious accounts.

“We should go on the next hike as soon as the snow melts,” he tells her. “When’s your spring break?”

“It’s at Easter, but Easter is early this year, at the end of March. It could still be very cold.”

“Then we’ll have to keep each other warm,” he smiles. And the date is set.

“So,” he says, “that settled, let’s have a look at what else the paper has to tell us today.” He turns back to the front page and glances at the headlines. “Well, we knew the trade negotiations with Germany would fail, so that’s not news.” He fails to notice a piece of paper sliding from between the pages and falling to the floor.

Gisi picks it up. “Look at this, Max,” she says. “It’s a speech by Hitler. Someone seems to have printed out the whole thing and tucked it between the pages of the paper.”

“Hm. Somebody is getting ideas from us.”

“Shh. This speech was given a couple days ago, on the fourth anniversary of Hitler’s coming to power. Listen what he says here.”

Max leans in and she reads aloud.

“And I can prophesy here that, just as the knowledge that the earth moves around the sun led to a revolutionary alternation in the general world-picture, so the blood-and-race doctrine of the National Socialist Movement will bring about a revolutionary change in our knowledge and therewith a radical reconstruction of the picture which human history gives us of the past and will also change the course of that history in the future.”

“The blood-and-race doctrine of the National Socialist Movement,” repeats Max. “Horrifying words. On top of the blood-and-race problem, he uses the full name of his wretched party, which dares to co-opt our name, Socialist.”

Gisi wrinkles her nose. “Well, I don’t feel so proprietary about that, to be honest. If they want to call themselves Socialists, let them be socialistic. Populists like to make promises like income equality, so let the state take care of all its people, not just those with the right blood. It’s not the Socialist part of the National Socialist Movement that bothers me. It’s the Nationalist part. Now, listen to what he says next:

‘And this will not lead to an estrangement between nations; but on the contrary, it will bring about for the first time a real understanding of one another. At the same time, however, it will prevent the Jewish people from intruding themselves among all the other nations as elements of internal disruption, under the mask of honest world-citizens, and thus gaining power over these nations.’”

“Well, there it is” says Max. “He doesn’t mince words, our countryman.”

Gisi is still reading. “His defense of the Nazi takeover as a bloodless revolution is pure propaganda, too,” she points out. “He says there wasn’t even one window broken, but his compatriots here in Austria don’t seem to feel such reticence.”

Max says, “What bothers me is how he returns again and again to the way conditions have improved in Germany over the last four years. Here he says:

‘Within a few weeks the political debris and the social prejudices which had been accumulating through a thousand years of German history were removed and cleared away.

May we not speak of a revolution when the chaotic conditions brought about by parliamentary-democracy disappear in less than three months and a regime of order and discipline takes their place, and a new energy springs forth from a firmly welded unity and a comprehensive authoritative power such as Germany never before had?’”

Gisi agrees. “Yes, those are the parts of the speech that will resonate with readers of the Kronen Zeitung in particular. Most of this speech is too high-flown for the ‘folk community’ he refers to but the message is clear.”

“Yes. Get rid of the vermin Jews, destroy democracy, and everyone will live happily ever after.”

“I’m so glad we got Wilhelm der Wandersmann’s article printed. Herr Wandersmann has plenty of work to do.”

‘And we should have our suitcases packed,” Max says.

Red Vienna in the news

Well, that title is a little deceptive on my part. Red Vienna is indeed in the news, but it’s the historical period, not my book.

Still, take a look at how much interest there is in that brief utopian experiment right now, especially in the social housing model that plays such a big role in my book.

And then read my book.

A couple days: a lecture

A week ago:

The February Uprising

https://www.msn.com/en-gb/news/world/the-february-uprising/ar-BB1iaDSR

Social Housing in Red Vienna

In the last few month or so:

https://jacobin.com/2023/11/otto-bauer-austro-marxism-nationalism-theory-history

https://businessdesk.co.nz/article/the-life/viennas-public-housing-is-a-paragon-for-the-world

https://delano.lu/article/red-vienna-a-model-for-lenert-

So much to read!

Red Vienna – a surprising launch into an unpredictable world

It’s the reddest day of the year—Valentine’s Day. Last night, Tom and I, together 35 years now, went out to eat at the very beautiful Au Jardin des Saveurs. It was a delightful evening in every way. When we got home, I checked my email and discovered that, though I was still patiently waiting to hear from the publisher, Red Vienna is already available through Amazon, in the US in hard or soft cover, overseas as an ebook.

An anticlimactic launch, to be sure! Nonetheless, I’m thrilled that you can buy it, in hard or soft cover in the US, or as an ebook there or overseas. And do have a look at its website.

I’ve been completely immersed in the second volume, Underground, which is more than halfway done now. It’s the end of 1936. I work on it as long as my neck and shoulders will let me type, go to sleep thinking about it and wake up the next morning thinking about it again. The characters are now back in Vienna, secretly working for the Social Democratic party in the face of continuing persecution and an unchecked rise in anti-semitism. I’m in a research phase, reviewing the history of Vienna in 1937 by rereading my parents’ copy of George Gedye’s book, Betrayal in Central Europe, and combing through the New York Times archives of that year. Next on my list is Bruno Kreisky’s The struggle for a democratic Austria. Lots of notes to take.

Now, I think I’ll have to take a break to get the word out that Red Vienna is available. Hurray!!