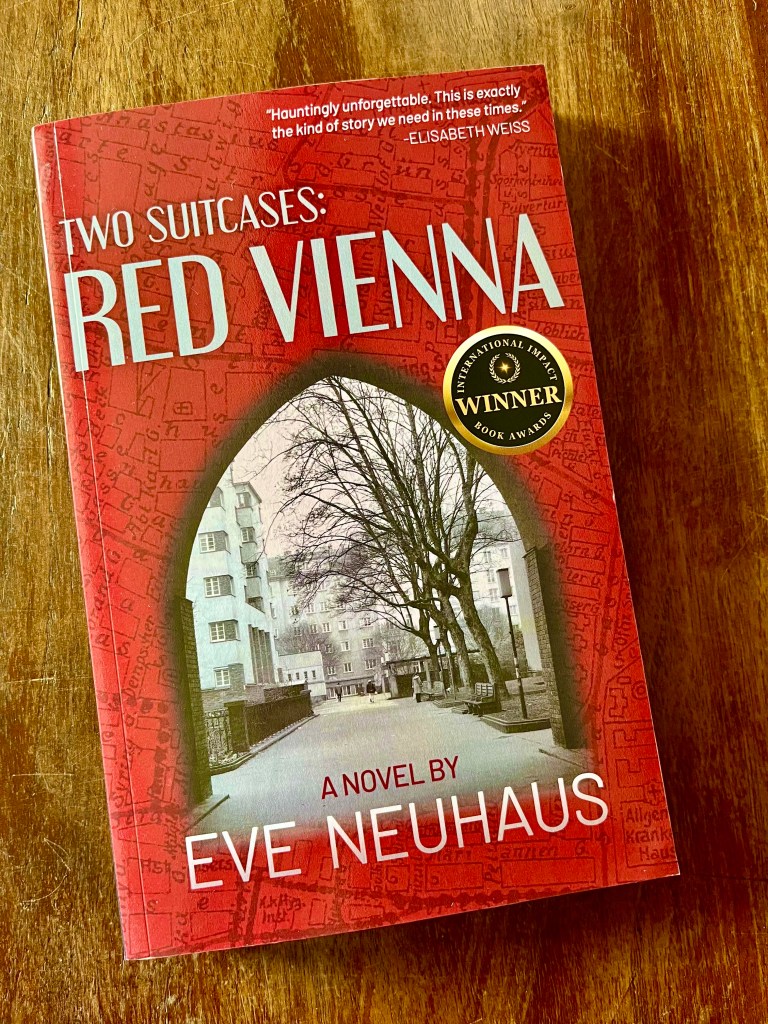

This seems like the right day to share the Rosh Hashanah section of Underground, the second volume of Two Suitcases, which is currently being considered by agents.

May the new year bring you many moments of joy and small delights. May we all find the courage to stand up for our neighbors, the strength to resist instead of bending to dark forces, and the flexibility to let go and move on when it’s necessary.

And, even in the dark times, let there be singing. (paraphrase of Bertolt Brecht)

Shana Tova.

UNDERGROUND

Chapter 26

THE NUREMBERG LAWS

September 16, 1935

10 am

Basel

Emil picks up a copy of the Der Bund at a kiosk before boarding the morning train to Vienna. If all goes well, he’ll arrive in time for the festive meal his mother will have ready at sunset to celebrate Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year.

Seated by a window, he reads the headlines about some laws that were announced the day before at the Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg.

ANTI-JEWISH LAWS PASSED IN GERMANY

Non-Aryans deprived of Citizenship and Right to Marry

Hitler warns that Provocative Acts will draw Reprisals

Two laws have been enacted, the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor, and the Reich Citizenship Law.

The first of them bans marriage between Jews and non-Jewish Germans, criminalizes sexual relations between them, and prohibits Jews from employing German women under the age of 45 as maids.

The second defines who the first law applies to. Only individuals of “German or kindred blood” can now be citizens of Germany. Jews are relegated to the status of “subjects of the state.” The new law defines a Jew as anyone with three or more Jewish-born grandparents, including converts to Christianity and children and grandchildren of such converts.

Emil expected the news to be bad but he’s still shocked to see the prohibitions in black and white. Between his regular features, his red hair, and his apparent disinterest in religion and politics, Emil is rarely identified as a Jew, and, to be honest, he rarely identifies himself as one. The Swiss people with whom he works assume he’s a Catholic Austrian, and he hasn’t disabused them. But this news from Germany shakes him to the core. He wouldn’t be safe in Germany, and if Germany takes over Austria, of which there is talk, his family will not be safe in Austria.

What a blow to Jews, particularly on the eve of the most holy days of the year, he thinks. Rosh Hashanah begins that night and will be celebrated for two days. A week later comes the day of atonement, Yom Kippur, when Jews fast, the most sacred ritual of the year. He puts the newspaper down and closes his eyes. It’s good that he’s on his way home—he wants to be with his family.

In the seat behind Emil, two businessmen, one Swiss and one Austrian, are talking.

“They’ve changed the flag in Germany, did you see that?” says the Swiss.

“No, to the Swastika?”

“Yes, on a red background. It doesn’t surprise me. Hitler says his Reich will last a thousand years, so naturally he would put his own flag in place.”

The Austrian is nonplussed. “I read that they’ve formally downgraded the Jews to non-citizens. Not a bad idea, if you ask me. They’re not so much of a problem in Switzerland, but in Germany—and in my own country—the Jews have had far too much power for too long.”

“In what way?”

“In the universities, for a start, and in banking, of course, but it’s far more than that. For years, the Jews in Vienna have controlled the discourse. They’ve set the tone for what people think! They decide what’s good and what’s bad. That’s the real reason the Germans are smart to do what they’re doing.”

The Swiss man isn’t convinced. “I don’t buy it. Why would a strong, intelligent people like the Austrians let that happen?”

“I’m sure if they knew it was happening they wouldn’t have agreed to it. But the Jews are sneaky, and they have international connections that quietly help get them into positions of power.”

“I’ve heard those arguments before, but I don’t understand why it should be true in Germany and Austria, but not in Switzerland.”

The Austrian man’s lip curls. “It is, my friend. You and your countrymen choose not to see it.”

Emil shudders.

* * *

Leopoldstadt

A few hours later

Emil puts his suitcase down on front of his parents’ door, and takes in the enticing smell of his mother’s cholent filling the hallway. The savory bean stew with bits of meat and potatoes has always been his favorite. This is the first time he’s been home since April, almost half a year, and the smell of the cholent makes him happy he came. He just hopes he won’t find his parents, Ottilie and Richard, in exactly the same positions in which he left them, his mother chattering nervously in the kitchen, his father slouching in his chair, ignoring her.

In fact, when his father opens the door, Ottilie is busy in the kitchen and the state of the living room indicates that Richard had just risen from his chair when Emil rang the doorbell. But things have changed. The place is much cleaner. The untidy piles of newspapers on the dining room table have been replaced with a tablecloth.

An hour later, as Ottilie is putting out place settings, the doorbell rings again.

“Tante Stefi! Nathan!” Emil is pleased to greet his mother’s sister and her son, his cousin Nathan. “I didn’t expect to see you!”

“We couldn’t stay away from you forever,” Stefi says, patting Emil’s cheek as if he were a small child. “No matter what your father did.”

“Mutti! You promised not to make remarks like that!” Nathan, nine years younger than Emil, will be entering university this fall if Emil’s calculations are right. The cousins haven’t seen each other since the bank failure five years ago, when Richard’s part in the mismanagement of the Creditanstalt Bank led to its collapse, and took Ottilie’s family fortune—and that of many other Jewish depositors—with it. The scandal had split the family, with Stefi’s husband refusing to speak to Richard since then. Nathan was a child at the time. Now he’s almost a man.

Richard speaks up, a false heartiness making his voice too loud. “Welcome, welcome! L’Shana Tova!”

New Year’s greetings are shared all around, the guests’ coats hung on the coat tree, and the family makes themselves comfortable around the table. The men put on their yarmulkes and Emil’s father, his tallit, or prayer shawl.

Ottilie emerges from the kitchen to light the candles and say the opening blessing, and Richard follows by blessing the wine. The blessing of the Challah, a beautifully braided loaf of bread glistening with egg wash, fresh from the oven, is next.

As everyone takes a piece of the bread and dips it into honey to celebrate the sweetness of life, Emil comments,

“Not such a happy new year for the Jews in Germany.”

Bread and honey in their mouths, no one says a word.

Next, slices of apples are dipped in the honey, and Emil smiles along with everyone else as the blessing is chanted and wishes for a sweet new year are exchanged. Carp in sulz, fish in cold jellied broth, is the next course.

Between the prayers and the sharing of ritual foods, the family catches up on the news. Nathan will not be attending university although he has been preparing for it for years. Instead, he will be a clerk in the bookshop owned by one of his father’s cousins. No one asks why his father isn’t there—they all know he blames Richard for the whole family’s financial difficulties.

Then the real meal begins. Ottilie brings everyone some homemade chicken broth with two matzo balls in each bowl.

Stefi is surprised. “Matzo balls! But it’s Rosh Hashanah, not Pesach!”

“It isn’t so often I have my whole family here,” Ottilie says. “I made all of Emil’s favorites. I want to lure him back to Vienna!”

Emil smiles at her. “So far, so good.”

Three more times through the long meal he tries to talk about the Nuremberg Laws, and three more times he’s shut down by one or more of his relatives.

Chapter 27

MAKING AMENDS

September 17, 1935

late morning

Café Josef Weiss and Café Central

After the morning service at the synagogue, Leo and Felix walk over to their regular café, where they find Anna, Max, and Hugo standing beside the locked door.

“I guess they don’t work on the Jewish holidays either,” Anna says. “But why don’t we go somewhere else? I’m sure the cafés in the Inner City are all open.”

So it is that most of the group is at Café Central when Emil walks in. Warm greetings are exchanged and Emil joins them at their table.

“So,” Felix says, “who went to synagogue this morning?”

“I did,” says Emil. “The singing was outstanding. There’s a new cantor at my family’s temple.”

Leo looks around the circle, his head cocked. “Nobody else? Yet none of us went to work.” He raises his bushy eyebrows. “Felix and I went with the family. I enjoyed the music too—the fellow who blew the shofar did a particularly impressive job—but it was the rabbi’s talk that will stay with me.”

“And so?” asks Hugo.

“He brought up a tradition that I had either forgotten or isn’t often followed. In the eight days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, it is our responsibility to make amends.”

Anna interrupts. “We all know that. It’s nothing new.”

“But this rabbi suggested that we take the project much more seriously, that we go and knock on the doors of the people we may have wronged, and apologize face to face,” Leo says.

His brother adds, “I think it’s a good idea. I’m planning to do it. Is anyone else up for the challenge?” He lights a cigarette and looks at each of the others questioningly.

“It’s not for me,” Max says. “I wouldn’t want to take the chance that my apology wouldn’t be accepted. I could have a big argument on my hands.”

Anna thinks for a moment and then says, “I think it’s a very good idea. It’s excellent psychology. Everyone feels better after Yom Kippur because you get rid of whatever guilt you were feeling. Confession in Catholic Church does the same thing. Taking the trouble to face the people you may have hurt or caused problems for makes a big difference to everyone involved. I’m in, even though I almost never take religious customs seriously.”

“Really?” says Max, incredulous. “You are my sister Anna, aren’t you? And not her long-lost twin?”

Anna scoffs.

Max turns to the others. “Have any of you ever heard my sister apologize to anybody about anything?”

A ripple of laughter spreads around the table. Emil raises one finger. “I have.” He looks at Anna. “We were walking in the Heiligenstädter Park, arguing.” He crooks an eyebrow at Anna as if to say, do you remember? “I was defending Karl Lueger, the Christian Socialist mayor who built so much of Vienna’s infrastructure, and you were rightly calling him a populist and an anti-Semite. I said it didn’t matter, the city was better because of what he did, no matter what his politics were. The argument ended when you apologized, as I recall, and admitted I was right.”

“That is certainly not how I remember it!” cries Anna, dark eyes flashing. “As I recall, we came to the end of the park and I said, ‘Let’s not argue anymore—let’s talk about something else.’”

Emil looks down his nose. “I don’t think so. But let me be the one to say ‘let’s not argue’ this time. And let me apologize for remembering the incident differently.”

“No,” says Hugo thoughtfully, “I don’t think that’s the kind of apology the rabbi meant. As my mother used to say, apology is cheap currency. It’s easy to apologize without meaning it because it doesn’t cost anything.”

Emil is surprised. “But I’m genuinely sorry, Hugo. It doesn’t count if you haven’t stewed on the offense first?”

Felix answers. “Emil is right, Hugo. Both kinds of apologies are effective so long as they’re sincere.”

Anna doesn’t give anyone else the chance to respond. “But apologies can also be used to get one’s way! Willi is a master of it!” She grimaces, thinking of the little boy she’s caring for. “He does something truly terrible, like hitting another boy,” she throws up her hands in frustration, “and then he apologizes to the other child—and to us, and his teachers, and to the injured child’s parents—and it all sounds perfectly sincere! He looks like he really means it.”

“He’s learned how to put on exactly the right face,” agrees Hugo. “In fact, he can be so believable that I’m taken in every time. I think he’s making sincere promises, from the bottom of his tough little heart, and I give him another chance.” He snorts, blowing cigarette smoke out of the corner of his mouth.

Anna continues, “But afterwards he can never manage to keep up the good behavior, no matter what his intention is. He always slides back. Poor Willi.” She sighs. “He’s only 10.”

Of the five men at the table, only Hugo looks at Anna sympathetically.

Emil is admiring the line of her chin and her high cheekbones. He finds her especially attractive when she’s passionate.

Max is fuming silently. In his book, Anna is sharing one more reason why Willi needs to move on.

“So, is Anna the only one taking up the challenge, then? Is it just the two of us? Leo?” asks Felix after a pause.

In the end, Max is the only one who doesn’t agree to make amends that week.

As they get up to leave, Emil and Anna make a date to meet again in two days.

* * *

September 19, 1935

late morning

Café Landtmann, Vienna

Anna arrives at the café 10 minutes early and immediately orders a coffee. She prefers to pay her own way, even though she knows Emil can well afford to pay for them both. The fact that she has barely begun a new job as an office clerk after more than a year of not working doesn’t change how she feels.

As she inhales the scent and sips the coffee very slowly, she notices an older, neatly bearded man talking to a younger man at the next table. Can it be Professor Doctor Freud? It isn’t the first time Anna has seen him—she heard him lecture at the university several times—but that was always from a distance. She listens carefully. If she isn’t mistaken, he and the younger man are talking about cigars.

Doctor Freud lights one and breathes in the smoke contentedly. The younger man speaks.

“Of course you are aware of the recently enacted Nuremberg Laws in Germany, Herr Professor?”

“I am, and I find it most concerning.” The older man moves his jaw in a peculiar way as he speaks.

“Professor, you are Jewish. If Germany were to annex Austria, as Hitler desires, would you go to Palestine, as so many Jews have? I know you stated a few years ago that you didn’t support establishing a Jewish state in Palestine.”

“That’s correct, and I stand by my words. I don’t think that Palestine could ever become a Jewish state, or that the Christian and Islamic worlds would ever be prepared to have their holy places under Jewish care. It would seem more sensible to me to establish a Jewish homeland on less historically-burdened land.”

At that moment, Emil slides into in the chair opposite Anna. She’s was so engaged in Freud’s conversation that she didn’t even notice him entering the café.

“Anna,” he says without greeting her formally, “I want to apologize more fully.” He leans forward, puts his elbows on the table, and looks at her intently, a crooked smile on his face.

She pulls herself away from Freud’s words, and turns to Emil, tipping her head toward the psychologist and discreetly pointing with her finger.

Emil glances at Freud and mouths “Freud?”

She nods “Yes!”

But the moment is gone. The professor and the young man are standing and then moving toward the door.

Emil and Anna sit and talk at the café all morning. He begs her pardon for having acted superior and not always listening to her. She begs his for having gotten angry too quickly and for her own variety of acting superior.

He tells her about some of his eccentric coworkers at Sandoz. She tells him about her boring office job.

“I spend my days sitting in a row with a dozen other women, all of us copying information from hand-written bills of sale into enormous ledgers, and then adding up column after column of numbers,” she says. “You can’t imagine how frustrating it is when the sums don’t come out right. I’m very tempted to leave them wrong.”

Emil raises both eyebrows. Anna continues, “I dislike the old crone in charge of us enough to be glad to get her in trouble, even though in the end, it would be me who’d get fired.” She pulls a piece of paper out of her bag. “Look. This is my boss.” She holds out a caricature of an angry older woman with exaggerated hawk-like features. “One of the other women drew it and gave it to me.” They both chuckle.

“It’s good!” he says. “I can imagine her perfectly.”

They go on to tell old stories, and they laugh until the man who has taken Freud’s table turns around and glares at them.

* * *

Felix and Leo begin the day by apologizing to their mother for all their boyhood antics. The family spends hours reminiscing, hooting with laughter, as one old story leads to another.

* * *

Hugo is shifting from foot to foot impatiently in front of Gert’s door when she returns from work.

“Gert, listen. There’s something I need to tell you. I realized that I take you for granted far too often. I am so sorry.” His words flood out.

Gert smiles a little as she inserts her key in the lock. “My goodness, what brings this on? Come in, come in.”

They sit at her table, and he tells her about the rabbi, and about the agreement between their Jewish friends to take making amends seriously. As he speaks, he realizes there’s more he wants to say. He takes a deep breath.

“I have another apology, too. Our relationship is years old now,” he says. “I should have asked you to marry me a long time ago.” Another breath. He looks down and then up, into her eyes. “Gert, will you marry me?”

Gert grins from ear to ear. “Hugo! Of course! I forgive you everything and yes, I will marry you!”

* * *

Max unpacks two radios and assembles three lamps that morning.

* * *

Later in the week, Emil and Gisi meet for a walk in the Stadtpark. Though they’ve agreed that nothing would change, it has. There’s a new distance between them, a slight hesitation before they begin to speak, more silences between their words.

He tells her about the apologies he made to some of his school friends, one who had completely forgotten the incident Emil was apologizing for, the other who remembered it very well and was surprisingly grateful to Emil for stopping by.

“And Max? “ asks Gisi. “Was he there when you all agreed to carry out this project to make amends? Because I haven’t seen him all week.”