I’m sure there are many reasons not to post the penultimate chapter of a work in progress before publication, but sometimes it feels to me as if the piece itself is begging me to get it out there now, on its own.

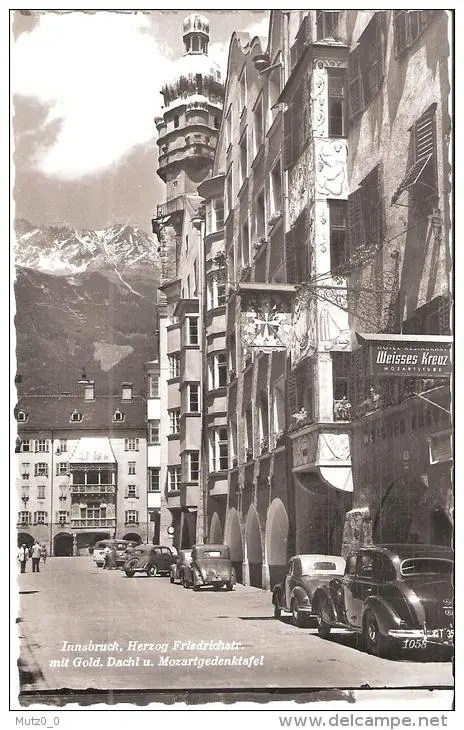

The chapter, “In the Company of Friends,” takes place on the day Austria gives up its independence and becomes part of Germany in March 1938, the day before Hitler marches triumphantly into Vienna, warmly welcomed by most Austrians.

I am posting it the day before Trump’s second inauguration.

The process and timing of writing Two Suitcases has always been more or less outside of my own volition. The parallels to events in the US aren’t something I look for and work at adding to my story. It’s the other way around. The story refuses to tell itself through me until the unfolding events push it to be told.

Those of you who’ve read Red Vienna or followed my blogs will be familiar with the characters and setting—I hope the chapter is meaningful even if you haven’t. Take the trouble to read it to the end, even if meeting the eight characters all at once is confusing. Don’t let the names of the Viennese foods trip you up either. They’re all described earlier in the story.

In brief, the young people in the group who come together in the chapter are all Social Democratic activists. For the four years covered in the second volume of Two Suitcases, they’ve been working underground to keep their vision of a kinder, more thoughtful, more equitable world alive. As Austria capitulates, most of them plan to go into exile.

Chapter 52

In the company of friends

Friday, March 11, 1938

early evening

Vienna

Gisi can hear the sound of Austrian State Radio everywhere as she hurries over to Max’s workshop, a covered bowl in a basket on her arm. There’d just been a radio announcement that the Plebiscite on Austrian independence had been canceled. Chancellor Schuschnigg would be making a major address to the country any minute, and Gisi wants to be with Max to hear it.

She’s not alone. Within the hour, nudged by a phone call or a knock on the door, everyone else in the group decides that they too would like to listen to the Chancellor’s speech in the company of friends.

At his shop, Max and Leo move a big table close to the best radio, and the others bring eight odd chairs and stools to put around it. Near the table’s center is Gisi’s bowl of Kaiserschmarrn, its sweet fragrance surrounding it, a jar of applesauce beside it.

Toni is warming some rind souppe on the coal stove. Its beefy aroma soon fills the little workshop and drifts into the store. On the workbench is a collection of bowls, cups, and spoons that Max brought down from his apartment, along with his last three cans of pickled herring.

Gert slices the loaf of black bread she brought and is putting it on the table when Hugo enters the shop with a smile and a swagger.

“Look!” he cries when all eyes are on him. He pulls a bottle from his bag. “Slivovitz! A full bottle of everybody’s favorite plum brandy! What is there to save it for?” Eight glasses and cups are quickly found and filled.

Leo contributes a block of Bergkäse cheese. Felix, looking apologetic, sets out a bit of butter, an almost empty jar of honey, and half a jar of Powidl.

“What do you expect?” he asks. “I’ve been imagining leaving my home every day for weeks. Why would I have any food there?”

The crowning glory of the table is an Obstkuchen, a buttery cake that Anna baked and decorated with dried apricots and cherries as the rays of a canned peach sun.

Felix is the last of them putting soup in his bowl when Max calls out, “Listen! Schuschnigg is about to speak!” as he turns up the volume of the radio. The music, a symphony by Beethoven, stops abruptly and the dignified voice of the Chancellor comes through.

“Women and men of Austria,

This day has placed us in a tragic and decisive situation. I have to give my Austrian fellow countrymen the details of the events of today.

The German Government today handed to President Miklas an ultimatum, with a time limit, ordering him to nominate as chancellor a person designated by the German Government, and to appoint members of a cabinet on the orders of the German Government. Otherwise German troops would invade Austria.

I declare before the world that the reports launched in Germany concerning disorders by the workers, the shedding of streams of blood, and the creation of a situation beyond the control of the Austrian Government are lies from A to Z. President Miklas has asked me to tell the people of Austria that we have yielded to force since we are not prepared, even in this terrible situation, to shed blood. We have decided to order the troops to offer no resistance.

I say goodbye with the heartfelt wish that God will protect Austria. God save Austria!”

The symphony resumes. No one says anything—they’re all in shock, though surely the announcement was inevitable.

Max rocks back and forth on his chair.

Gisi feels her tears rising.

Anna’s anger shows in her eyebrows and trembling lips.

Hugo begins to speak a couple of times but stops.

Beethoven’s music fills the shop.

Finally, Hugo raises his glass. “May God, or fortune, or whatever you believe in, protect us!” They each take a sip of the brandy.

Max looks at the table. “Let’s not waste this beautiful meal. Eat!”

“Wait,” cries Gert, “I have another toast.” She raises her glass again. “To friendship!”

Anna adds “And peace!” and they drink again.

Max glances at his empty glass. “Hugo, another round?” and Hugo pours out the last of the brandy.

Leo starts the toasts again. “To solidarity!”

“And to a kinder, more thoughtful, more equitable world!” adds Toni, and the last of the brandy is gone.

With bittersweet slowness, one by one, they pick up their spoons and begin to eat the rich, warm soup.

After savoring her second spoonful, Gisi speaks. “This is so good, Toni. But why did you make it today? Rinde soupe, especially with so much meat in it,is Sunday fare at our house.”

Toni smiles ruefully. “I made it for Leo. Before the Chancellor announced his resignation, I was planning to take it over to his place. I thought, I thought…” she stops and looks at Leo, who has already finished his soup and is wondering if there is more. Now he looks at her, his companion for so many years, and his eyes fill with sadness. She continues, “I thought it might be our last meal together—for a while, I mean—or our last meal in Vienna. Oh, I don’t know what I mean.”

Anna looks around the table. “It’s true, isn’t it? This will probably be our last meal together for most of us.”

“You aren’t the only one to feel that way,” Hugo says. “It’s why we all came.” He picks up a plate and fills it with cheese, bread, and several pieces of pickled herring. The others follow, until nothing is left at the center of the table but the sweets.

Suddenly, flickering light pours through the small window at the front of the shop and the boom of chanting voices shakes the room. Max runs to look out.

“It’s our neighbors,” he says, returning to the table. “Marching with torches and chanting Heil Hitler.”

“Oh, God,” Anna replies. “Why is it always so hard to believe the worst until it’s staring you in the face?”

“Listen,” says Gisi. “I have an idea. After we’re done eating…”

“If anyone can still eat,” Anna responds.

Gisi looks at her. “Try,” she says. “When our stomachs are full of this delicious food, I want us to do an exercise I did in one of my psych classes. Max, do you have some paper and pencils here?”

Max, his mouth full of bread spread with butter and Powidl, nods yes and points to the workshop.

“Anna, since you’re not going to eat, why don’t you help me out by finding the paper and cutting or tearing it into pieces about as big as…” she pauses to think, “as big as an Ausweis.”

“I’m eating,” Anna says, picking up a hefty piece of herring, putting it in her mouth, and chewing it slowly. “But I’ll do it later.”

The light and sound of the marchers fades into the distance.

“I suppose Miklas is in charge now that Schuschnigg has resigned,” Hugo muses. “Though Hitler probably has a successor in mind for the Chancellor’s position. Or maybe he’ll be Chancellor himself.”

Gert puts down her fork with a clatter. “Let’s not talk about it, Hugo. Let’s not talk politics for once.”

Hugo looks surprised and a little hurt. “Okay, what should we talk about then?”

Gisi is ready. “Let’s talk about the exercise I want to do.” She smiles as brightly as she can manage. “My professor gave us the assignment to make a list, in order of importance to each of us personally, of the five things we think matter the most.”

“In what sense?” asks Gert. “Do you mean things like money and housing? Or actions like pleasing your parents or doing work that makes you happy?”

“Yes, all of that, as well as qualities like patience and perseverance and generosity.”

“Okay, I’m ready to get the pieces of paper,” Anna gets up. “How many will we need?”

Gisi wrinkles her nose. “I think four per person will do. Max, can you find us all pencils or pens? Shall we do my exercise before cutting into Anna’s beautiful cake or after we eat it?”

“After,” says Felix, starting to clear the table. No one objects.

“Max, is there water down here? I’ll wash these plates and we can use them for the cake,” Leo offers.

A few minutes later the group settles down to make their lists, some at the big table, others scattered throughout the store, Max at his table in the workshop. Silence settles over them like snow.

Gert is the first to finish. “What shall we do with our lists when they’re done?”

“Put them on the table where everyone can see them,” Gisi answers. “There’s a second part of the exercise coming.”

When all the lists are finished and everyone has read theirs aloud, she says, “Now, on your second piece of paper, write down an action anyone can take to create a world in which the ideas or things you most value can be realized in their largest sense. For example, to promote the value of ‘Peace on earth,’ you could write ‘try to always be kind’ for the second round.”

“I get it,” Toni says. “I wrote down ‘my friends’ as a personal value, and I can think of dozens of ways to would promote friendship generally, like ‘appreciate everybody’s uniqueness’ or ‘think of others before yourself.’”

“That’s it. Try to make the action as universally useful as possible.”

An hour later, and after another round of the exercise, Felix is picking up the plates again. Every crumb of the cake is gone. Hugo is copying out the same list eight times onto eight pieces of paper. Each of the friends signs their name eight times.

Before they hug and say long goodbyes, they each have a copy of the actions tucked away in a safe place.

Take care of the old and the young, and those who have less than you – Gisi

Keep your sense of humor – Max

Be ready to let go. Remember what really matters – Anna

Hold your head high – Leo

Believe in magic – Gert

Breathe – Felix

Choose kindness – Toni

Hold onto your vision of a better world – Hugo