This one is from the second volume of Two Suitcases, which is called Underground. If you haven’t read the first volume Red Vienna yet, order it at your local bookstore or through Amazon.

February 2, 1937

a cafe not far from Max’s workshop

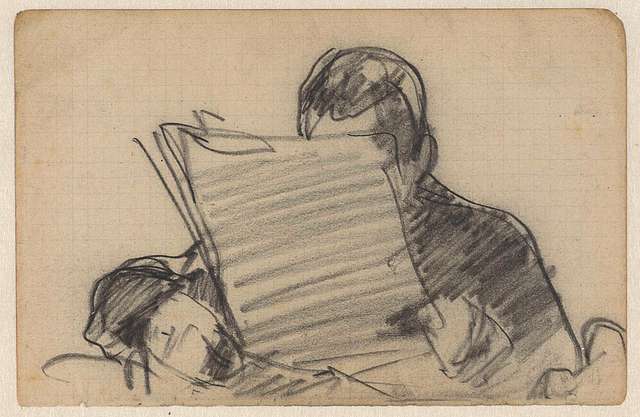

Gisi turns the pages of the new issue of the Kronen Zeitung she spread on the cafe table. She’d seen several copies on her way to the cafe. The paper’s populist touch allowed it to survive the Fascist takeover of Austria and keeps it on the newsstands in working class neighborhoods.

On the second to the last page, she finds what she’s looking for: From Innsbruck to Italy—Three Winter Hikes, by Wilhelm der Wandersmann. It’s Max’s and her first effort at hiding coded information about safe escape routes in the paper. She’s pleased to see it, of course, and she feels confident that no one who doesn’t know the code could possibly suspect anything, but it bothers her to think about the lies she had to tell to get it published .

The son of the publisher, a sweet but naive young man, now waits for her after lecture every week, or worse, he arrives early and saves her a good seat. Gisi puts on her spectacles to discourage him, but it hasn’t worked. She can’t tell him about Max so she told him that she’s helping a cousin in Tyrol to get a start in journalism instead.

“My cousin is more of an outdoorsman than a writer,” she’d said to him, “but he wants to write a series of articles like this about hikes all over the country. He’d like to make his love of hiking pay for itself. That’s why he’s using a catchy byline instead of his own name.”

What she feels worst about is that the day she gave the publisher’s son the article, she let him take her out for coffee and a pastry. Encouraging him even that much is so wrong.

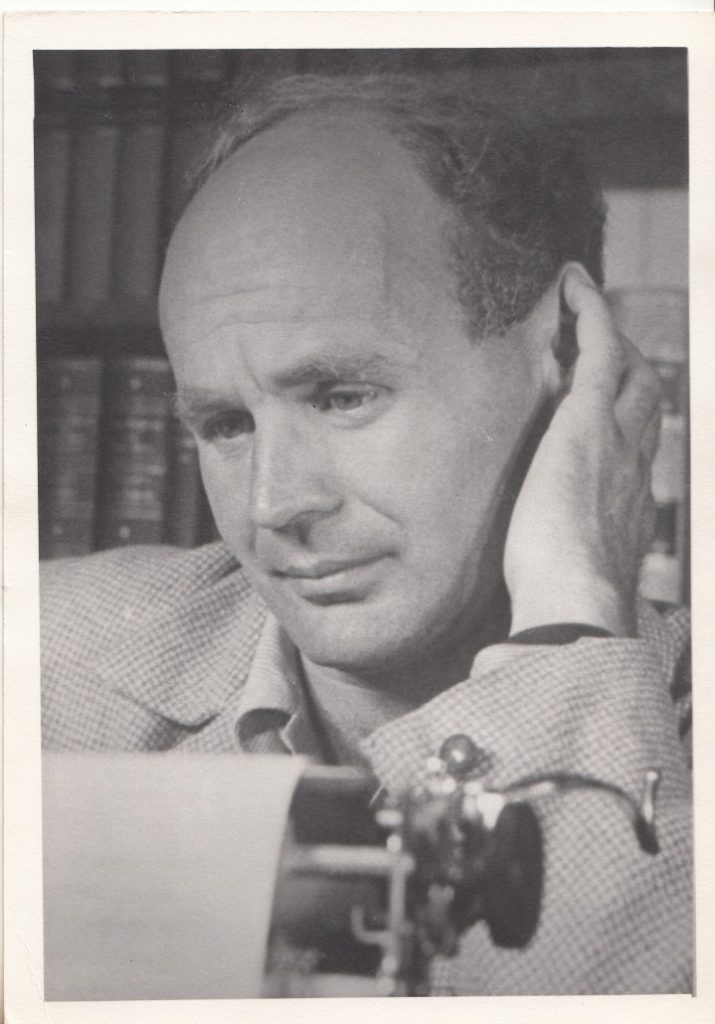

Max rushes into the smoky cafe. “Sorry I’m late,” he says breathlessly. “I sold another radio and had to pack it up. I only have two left now.” They kiss lightly. “So, let’s have a look at our man Wilhelm der Wandersmann’s article!”

The code isn’t complicated. It involves starting certain sentences with letters that indicate the political bent of the proprietors of inns and restaurants along the way. Each time Gisi and Max succeed in publishing another article, a new code will be shared, again in code, in the Arbeiter Zeitung.

“It’s fantastic!” he says, smiling broadly. “I can’t wait to take the next hike with you.” The next hike will be considerably longer with at least two overnight stays, quite possibly three.

Their conversation turns to how much fun they had hiking the trails for the article over the last six months, two of them more than once. In the end, they decided that only one of the three routes would be safe, and they’d written the article together, he injecting the humor into her fastidious accounts.

“We should go on the next hike as soon as the snow melts,” he tells her. “When’s your spring break?”

“It’s at Easter, but Easter is early this year, at the end of March. It could still be very cold.”

“Then we’ll have to keep each other warm,” he smiles. And the date is set.

“So,” he says, “that settled, let’s have a look at what else the paper has to tell us today.” He turns back to the front page and glances at the headlines. “Well, we knew the trade negotiations with Germany would fail, so that’s not news.” He fails to notice a piece of paper sliding from between the pages and falling to the floor.

Gisi picks it up. “Look at this, Max,” she says. “It’s a speech by Hitler. Someone seems to have printed out the whole thing and tucked it between the pages of the paper.”

“Hm. Somebody is getting ideas from us.”

“Shh. This speech was given a couple days ago, on the fourth anniversary of Hitler’s coming to power. Listen what he says here.”

Max leans in and she reads aloud.

“And I can prophesy here that, just as the knowledge that the earth moves around the sun led to a revolutionary alternation in the general world-picture, so the blood-and-race doctrine of the National Socialist Movement will bring about a revolutionary change in our knowledge and therewith a radical reconstruction of the picture which human history gives us of the past and will also change the course of that history in the future.”

“The blood-and-race doctrine of the National Socialist Movement,” repeats Max. “Horrifying words. On top of the blood-and-race problem, he uses the full name of his wretched party, which dares to co-opt our name, Socialist.”

Gisi wrinkles her nose. “Well, I don’t feel so proprietary about that, to be honest. If they want to call themselves Socialists, let them be socialistic. Populists like to make promises like income equality, so let the state take care of all its people, not just those with the right blood. It’s not the Socialist part of the National Socialist Movement that bothers me. It’s the Nationalist part. Now, listen to what he says next:

‘And this will not lead to an estrangement between nations; but on the contrary, it will bring about for the first time a real understanding of one another. At the same time, however, it will prevent the Jewish people from intruding themselves among all the other nations as elements of internal disruption, under the mask of honest world-citizens, and thus gaining power over these nations.’”

“Well, there it is” says Max. “He doesn’t mince words, our countryman.”

Gisi is still reading. “His defense of the Nazi takeover as a bloodless revolution is pure propaganda, too,” she points out. “He says there wasn’t even one window broken, but his compatriots here in Austria don’t seem to feel such reticence.”

Max says, “What bothers me is how he returns again and again to the way conditions have improved in Germany over the last four years. Here he says:

‘Within a few weeks the political debris and the social prejudices which had been accumulating through a thousand years of German history were removed and cleared away.

May we not speak of a revolution when the chaotic conditions brought about by parliamentary-democracy disappear in less than three months and a regime of order and discipline takes their place, and a new energy springs forth from a firmly welded unity and a comprehensive authoritative power such as Germany never before had?’”

Gisi agrees. “Yes, those are the parts of the speech that will resonate with readers of the Kronen Zeitung in particular. Most of this speech is too high-flown for the ‘folk community’ he refers to but the message is clear.”

“Yes. Get rid of the vermin Jews, destroy democracy, and everyone will live happily ever after.”

“I’m so glad we got Wilhelm der Wandersmann’s article printed. Herr Wandersmann has plenty of work to do.”

‘And we should have our suitcases packed,” Max says.