La vraie magie : des pierres noires, trois verres à vin et une bonne histoire

For several weeks, I’ve been watching for magic in my life. An explanation is in my post from two weeks ago, Peace, Love, and Magic. The post that follows it, The Queen of Cordes, is an illustration. And since then, my life has been filled with ordinary magic. It seemed as if all I had to do was hear about a problem, and a solution would appear. I found the keys my neighbor lost. I found the right person to care for a friend’s gîte. In record time.

Depuis plusieurs semaines, je suis à l’affût de la magie dans ma vie. L’explication se trouve dans mon billet d’il y a deux semaines, Peace, Love, and Magic. Le billet qui suit, La reine de Cordes, en est l’illustration. Et depuis, ma vie est remplie de magie ordinaire. Il me semblait qu’il suffisait d’entendre parler d’un problème pour qu’une solution apparaisse. J’ai retrouvé les clés que mon voisin avait perdues. J’ai trouvé la bonne personne pour s’occuper du gîte d’un ami. En un temps record.

So naturally, I thought last Friday would be a good day to go to Emmaüs, the best thrift store in the world. (I wrote a story about that too, Emmaüs in Carmaux).

C’est donc tout naturellement que je me suis dit que vendredi dernier serait un bon jour pour aller chez Emmaüs, la meilleure friperie du monde. (J’ai d’ailleurs écrit un article à ce sujet, Emmaüs à Carmaux).

“I feel lucky today,” I told the friend with whom I went to Carmaux. And indeed I was!

« Je me sens chanceux aujourd’hui », ai-je dit à l’ami avec lequel je me suis rendu à Carmaux. Et c’est vrai que j’ai eu de la chance !

Neither the round table nor the small carpet that I’ve been on the lookout for months was there—you don’t go to Emmaüs for specific things in any case—but in the kitchen section, in a heavy glass candy dish, was a collection of polished black stones. There were about twenty of them, different kinds, some that you could hold up to see a glint of light, others opaque, different shapes and sizes but all beautifully polished, ranging from the size of a marble to that of a walnut.

Ni la table ronde ni le petit tapis que je cherchais depuis des mois n’étaient là – on ne va pas chez Emmaüs pour des choses précises de toute façon – mais dans le rayon cuisine, dans un lourd plat à bonbons en verre, se trouvait une collection de pierres noires polies. Il y en avait une vingtaine, de différentes sortes, certaines que l’on pouvait tenir pour voir un reflet de lumière, d’autres opaques, de différentes formes et tailles mais toutes magnifiquement polies, allant de la taille d’une bille à celle d’une noix.

~

For years, I’ve been collecting black stones to give to people. Somewhere, a long time ago, I read that a black stone will absorb negative energy, particularly the negative energy you pick up from others. A useful tool, no? The trick is to state that you believe the stone can do it—black is absorptive after all—and then to hold the stone in the palm of your hand for a little while, concentrating on it. After a few seconds or minutes, the stone can be set aside. For a while, I was even sewing little sacks to keep the stones in.

Pendant des années, j’ai collectionné des pierres noires pour les offrir aux gens. Quelque part, il y a longtemps, j’ai lu qu’une pierre noire absorbait l’énergie négative, en particulier celle que l’on reçoit des autres. Un outil utile, non ? L’astuce consiste à dire que vous croyez que la pierre peut le faire – le noir est absorbant après tout – puis à tenir la pierre dans la paume de votre main pendant un petit moment, en vous concentrant sur elle. Après quelques secondes ou minutes, la pierre peut être mise de côté. Pendant un certain temps, j’ai même cousu de petits sacs pour y ranger les pierres.

It works. Maybe it works literally—who knows?— but it definitely works psychologically. The act of imagining negative energy being drained from you is enough to change your perspective from being “inside” of the negative state to being “outside” of it, and thus to disempower it.

Cela fonctionne. Peut-être que cela fonctionne littéralement – qui sait ? – mais cela fonctionne certainement sur le plan psychologique. Le fait d’imaginer que l’énergie négative se vide de vous suffit à modifier votre perspective, qui passe de « l’intérieur » de l’état négatif à « l’extérieur », et donc à lui ôter tout pouvoir.

~

When I found so many perfect stones at Emmaüs, I was overwhelmed. It was obvious that finding them was the reason I’d come.

Lorsque j’ai trouvé tant de pierres parfaites chez Emmaüs, j’ai été subjuguée. Il était évident que c’était pour les trouver que j’étais venue.

I took the glass bowl of stones, plus two wine glasses and two dessert plates—one with a cat on it, the other a pretty floral design—to two ladies who are the keepers of the kitchen section.

J’ai apporté le bol de pierres en verre, ainsi que deux verres à vin et deux assiettes à dessert – l’une ornée d’un chat, l’autre d’un joli motif floral – à deux dames qui sont les gardiennes du rayon cuisine.

“I don’t need the glass bowl,” I explained to them, so one of the women wrote up a chit for 1€ for the lot, and the other carefully wrapped the stones in a cone of newspaper. As I went out, the chit in my hand, I saw my wine glasses and plates being wrapped too.

“Je leur ai expliqué que je n’avais pas besoin du bol en verre. L’une des femmes a donc rédigé un bon de 1 euro pour le lot et l’autre a soigneusement emballé les pierres dans un cône de papier journal. En sortant, le chit à la main, j’ai vu que mes verres à vin et mes assiettes étaient également emballés.

Then I went to find my friend. As we walked toward the cashier’s office to pay, she remembered that another friend was looking for a washing machine, and there it was, clean, refurbished, just the right size for our friend’s apartment. After a flurry of texts, arrangements were made for the washer to be delivered on Tuesday.

Puis je suis allée retrouver mon amie. Alors que nous nous dirigions vers la caisse pour payer, elle s’est souvenue qu’une autre amie cherchait une machine à laver, et celle-ci était là, propre, remise à neuf, de la bonne taille pour l’appartement de notre amie. Après une avalanche de textos, des dispositions ont été prises pour que la machine à laver soit livrée le mardi.

I paid my euro and went back to the kitchen section with the receipt and the remaining part of the chit to retrieve my bag of goodies.

J’ai payé mon euro et je suis retourné au rayon cuisine avec le ticket de caisse et le reste du chit pour récupérer mon sac de friandises.

Alas, when the ladies looked, the bag with the other part of my chit stapled to it wasn’t there!

Hélas, lorsque les dames ont regardé, le sac avec l’autre partie de mon chit agrafé n’était pas là !

Apparently it had been given to someone else by mistake. The two women were most apologetic. But what could be done? The other customer was gone.

Apparemment, il avait été donné à quelqu’un d’autre par erreur. Les deux femmes se sont excusées. Mais que faire ? L’autre client était parti.

I chose something else worth a euro—three wine glasses.

J’ai choisi quelque chose d’autre qui valait un euro – trois verres de vin.

~

As magically as those beautiful black stones appeared in my life, they disappeared.

Aussi magiquement que ces belles pierres noires sont apparues dans ma vie, elles ont disparu.

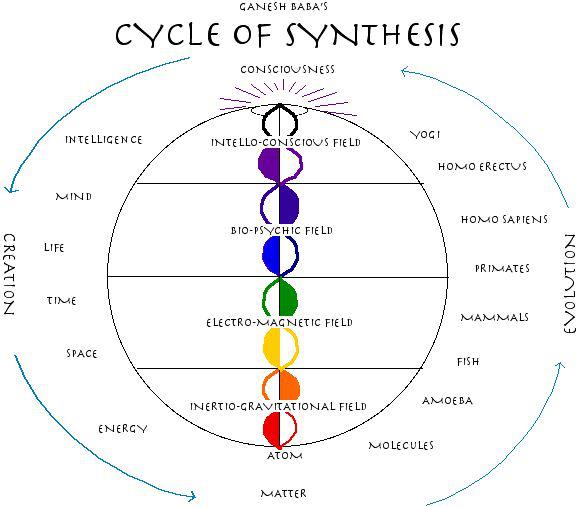

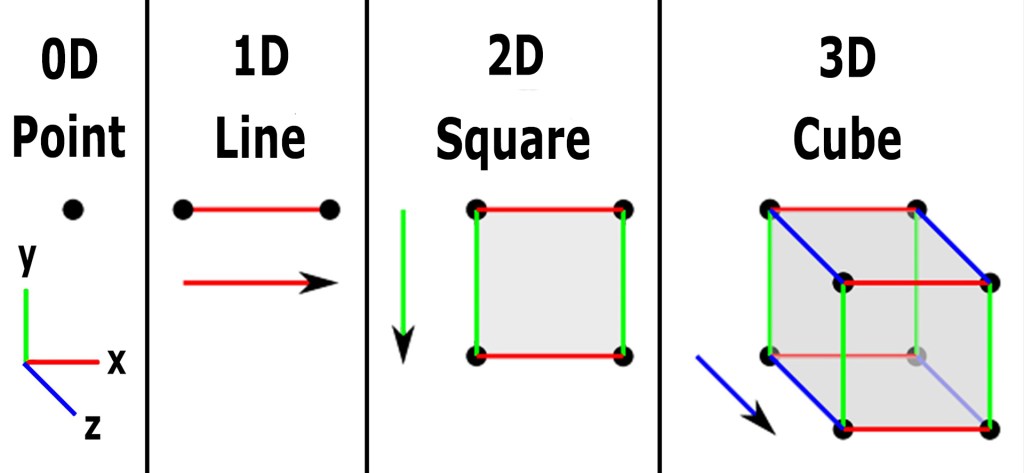

It’s such a delicate thing, magic, so ephemeral. It exists in the liminal space between the world of the physical and literal, and the worlds of thought and imagination, where time and space are transcended. I held those stones in my hands. Now they only exist in my memory.

La magie est une chose si délicate, si éphémère. Elle existe dans l’espace liminaire entre le monde physique et littéral et les mondes de la pensée et de l’imagination, où le temps et l’espace sont transcendés. J’ai tenu ces pierres dans mes mains. Maintenant, elles n’existent plus que dans ma mémoire.

It seemed like my extraordinary streak of good luck was over—until I realized that we’d found a washing machine for our friend, and I’d come home with something, too: three wine glasses and a story.

Il semblait que ma chance extraordinaire était terminée – jusqu’à ce que je réalise que nous avions trouvé une machine à laver pour notre ami, et que j’étais rentré à la maison avec quelque chose, aussi : trois verres à vin et une histoire.

On my way home, I recounted the story to a neighbor who was feeling particularly exhausted. She got it, and I left her smiling.

En rentrant chez moi, je l’ai raconté à une voisine qui se sentait particulièrement épuisée. Elle a compris et je l’ai quittée en souriant.

A good story can be very magical indeed.

Une bonne histoire peut être très magique.