I haven’t had much time to write lately. What with watching Éva, charming but nonetheless 19 months old, up to five days a week; sorting and emptying this enormous house and getting it ready for the market; hosting a slew of wonderful guests, some paid, some not; and best of all, having our whole, hilarious family here for over a week, entailing regular meals for between 15 and 23 guests (impossible without the help of my sister-in-law, Joanne Currie), quiet moments are scarce.

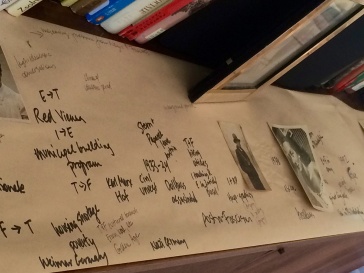

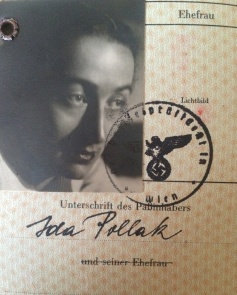

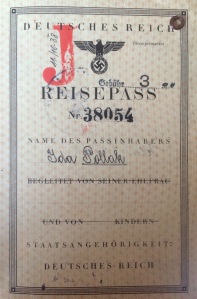

AND YET, the ancestors haven’t let up on me. Material floods in. My parents’ papers from Vienna, Paris, and Verfeil. Above, their identification papers from Tarn-et-Garonne, in France. Below, a history of the Social Democratic Party in Brigittenau, the neighborhood in Vienna where much of what I’m currently writing takes place:

I’m overwhelmed with gratitude.

Here’s a draft of the section I managed to write during all the uproar of the last couple weeks.

July 12, 1929

Vienna

Gisi looks into the old mirror on the inside door of the armoire and straightens her red tie for the fifth time. Her new blue shirt looks good but the tie isn’t hanging quite right. She wants everything to be perfect. Finally the tie is right. She takes Mitzi, the pipe cleaner antelope her grandmother made, from her shelf in the armoire and slips her into her pocket. Mitzi always comes along to important events. Moments later, Gisi is hurrying down the stairs to catch the streetcar to the Heldenplatz for the opening ceremony of the Second International Socialist Youth Congress.

The sight that meets her as she steps out of the car is stunning. As always she is early – but the huge plaza in front of the Hofburg Palace is already filling with many thousands of young people. Troops of children, from seven years up, their leaders, and throngs of young adults are pouring from every direction, following and clustering around red flags in a variety of shapes and sizes.

All the same beautiful deep red, the flags symbolize International Socialism. At the entrances to the courtyard and on the steps of the palace, tall, narrow flags flutter from very high poles. Similar narrow flags are scattered across the plaza, but most of the thousands and thousands of flags – everyone is carrying one – are simple rectangles of red. Each group carries at least one to which they’ve added a symbol to identify themselves, but the great majority are just red. It is so inspiring! As Trude winds her way through the sea of color and eager young faces, she’s filled with the excited energy of the crowd.

“Hi!” she calls out, waving her arm at Leo and Felix when she spots them on the steps to the Federal Chancellery, where their group is gathering. The brothers got up at four in the morning in order to stake a claim on this fine spot. “How great! We have a perfect view!” Gisi says. She climbs up a few more steps to survey the plaza.

Never before has such a group gathered.

“You won’t be able to stay up there,” Leo tells her. “Those steps are reserved for functionaries more important than our little group of event coordinators.”

“It’s remarkable!” says Felix, his eyes never leaving the gathering attendees. “It’s like an enormous symphony orchestra!”

Max and Anna arrive next.

“We were just at the station,” says Max. “What a welcome we gave! A good-sized brass band was there and they were playing loud, but we young people were even louder. As the train pulled in, we formed a long, broad wall along the tracks, and waved and chanted ‘Friendship, Friendship!’ You should have seen the eyes of our comrades on the train!”

Next come Hugo and Gert, she, in the new spring coat she made for herself out of offcuts from the dressmaker’s shop where she works.

“It’s beautiful!” says Gisi, seeing the coat for the first time. “You’re so creative with so little!”

“That is truly a compliment,” Gert replies. “Your mother is the queen of creative reuse! And you’re no slouch yourself.” Gisi smiles and turns a little to model her grey skirt, recently an old coat, swinging it outward gently to let the red trim show.

“Thanks! I’ll never be as good a seamstress as my mother, though,” she says. “I can’t compete. That’s why I worked so hard to get into Gymnasium.”

“That’s not true. You’re so smart! You’d be bored being an apprentice like me.”

“I don’t think I’d mind if I could work for someone else in a big shop like you do. But I would have to work at home for my mother! I wouldn’t be able to stand it!”

“I understand perfectly!” Gert laughs.

The group is talking animatedly as the musicians seat themselves on the large balcony above the palace entrance. Then Anna looks up in surprise.

“Emil!” she cries out. “You came!”

“Would it be alright if I join you?” asks Emil.

“You aren’t part of our group,” says Hugo. “You really shouldn’t…”

“Why not?” Anna’s voice cuts sharply over Hugo’s. “Everyone, let me introduce my friend from the University, Emil Bloch. Emil, these are my friends in the events coordination group I told you about. Hugo Preis, the rude one there,” she glares at Hugo, then goes on, “and Gert Braun, his girlfriend, Leo and Felix Goldfarb, my brother Max of course you know, and this is Max’s girlfriend, Gisi.”

Emil subdues his inclination to flinch at her boldness, and nods and smiles at each one of Anna’s friends. “Glad to meet you,” he says. Only Gisi notices his discomfort with the way Anna spoke over Hugo; she feels the same way herself.

The orchestra begins with Richard Strauss’s “Festival Procession.” By the time they finish and the chorus joins in for the “Wake Up” from Wagner’s Meistersinger, every heart in the massive plaza is joined to every other.

The hope of a new world is gathered.

Otto Felix Kanitz, founder of the Red Falcon scouts and head of the progressive Kinderfreunde school at the castle, Schönbrunn, greets the Future of Socialism, standing in the plaza before him. Karl Seitz, the mayor, welcomes them all to Red Vienna, living proof that a City of the People, For the People, is possible. The Dutchman Koos Vorrink, speaking for the International Youth Movement, announces that internationalism, the Internationale, the greatest conception of what humanity can be, is alive and flourishing. The orchestra is drowned out by the enormous cheer that rises from the crowd as the red flag of International Socialism is carried up onto the dais.

In the afternoon, guided tours of Vienna are offered, and most of the young people spread out over the city in small groups, visiting the social housing complexes as well as St. Stephen’s Cathedral, the Opera House, and other sights. The event coordination group splits up to prepare for the twenty-five concerts, celebrations, and performances that will be offered all over the city that evening.

Anna is the leader of the group preparing for Josef Luitpold’s poetry reading in the large meeting room at Karl-Marx-Hof that evening. She intends to get there at 6, but how can she refuse when a group of her friends says they were going to a café for a drink and a bite to eat?

“Hey, redhead, you come too,” one of them calls to Emil as he links arms with Anna and pulls her along.

Emil is very entertaining on a couple of beers –Anna already knows that. An hour passes in laughter as comical imitations of the morning’s speakers mix with deep appreciation of the Youth Congress so far. The sheer numbers! The power of the language: “a City of the People, for the People.” And how tightly organized the congress is!

Oh my! Anna realizes that she should have left for Karl-Marx-Hof ten minutes ago.

“I’ll find something for you to do, Emil,” she says over her shoulder as she hurries down the street. “But you really should have decided to come when I first invited you. We would have found a good job for you.” He catches up with her. For a few moments, their long strides match.

“I’m usually good at making myself useful wherever I am. What still needs to be done before the bard declaims?” he asks.

“Just tag along and I’ll see when we get there.”

They board the tram together.

Gisi arrives at Karl-Marx-Hof and heads straight to the large meeting room. The room is unlocked, and but no one is there. She looks at her watch: half an hour early. All the way over, she worried she would be late. Well, she is not.

The high-ceilinged room is lovely in the late summer afternoon. The windows are open wide, letting in a pleasant, fresh breeze. Summer sun fills the space and bounces off the glistening wood floor. At the front, the podium is already on the dais. Banners hang on all the walls. Hundreds of folding chairs are neatly stacked on wheeled carts lined up along the back wall.

The center of the room is gloriously open.

As quietly as possible, almost on tiptoe, Gisi crosses the huge room. She hangs her bag on the back of a folding chair, squints to look at the whole room, and then checks her watch again.

Humming the Skaters Waltz to herself very softly, Gisi begins to glide around the perimeter of the room, sliding on the highly polished floor as if she were skating. After just a few bars, she realizes how much more smoothly she could glide if she weren’t wearing shoes, so she pauses, unbuckles her sandals, and slips them off. Looking at her watch one last time, she leaves her shoes under the windows, and begins the waltz again. Her thin stockings slide beautifully.

This time she sings out the melody, dah, dah, dah, dah! Soon she leaves the edge of the room and glides across the middle. Then she skates around happily, making figure eights and graceful curves, singing all the time, until she notices with a shock that someone is standing in the door watching her.

It is Emil, who arrived at Karl-Marx-Hof with Anna a few minutes ago.

“Go ahead of me, Emil, and go and see if we need to turn on the lights in the large meeting room,” said Anna, who needed to stop in at the office first.

When Emil gets to the large meeting room, it is filled with light, and a fairy, some lithe little thing in a blue blouse, a pretty skirt, and stocking feet, is dancing around the room alone, accompanying herself with a slightly off-key version of Skater’s Waltz.

He is instantly enchanted. Should he announce his presence? Surely she will see him on one of her turns. In the meantime, he takes in the sweetness of this young girl dancing by herself so beautifully.

When she sees him, Gisi is mortified. Her heart pounds and blood rushes to her face. A man saw her being so silly!

Without retrieving her shoes, she heads toward the door to see who it is. When she realizes it’s Anna’s friend Emil, she’s even more upset. He must be at least Anna’s age – what, 20? – and he stood there watching her make a fool of herself. When did he come? How long was he watching her? Suddenly she’s angry. How extraordinarily impolite of him!

Breathing heavily, she stomps over to where Emil is leaning in the doorway. How dare he look so relaxed, so nonchalant? His long limbs remind her of a grasshopper.

“Why are you here?” she asks bluntly. She is standing firmly in front of him, hands on her hips, looking up. He’s a head and a half taller than she. “Didn’t Anna tell you the poetry reading doesn’t start for another hour and a half?”

“Anna sent me up here to turn the lights on for that very event,” says Emil. “It seems it isn’t necessary.” He smiles at the fire in her eyes.

Footsteps echo from down the hall.

“Ah, here is the great leader herself,” he finishes, looking down the hall and calling out, “Anna, Gisi is already here!”

“Gisi! Well, there are three of us. Let’s set up the chairs,” says Anna, entering, brisk and businesslike, apparently not noticing Gisi’s stocking feet.

Gisi gets to work, grabbing her sandals as discreetly as possible as she passes the windows, and scrambling to put them on while Emil and Anna are talking.

Soon the rest of the group arrives, all of the three hundred chairs are set up and coffee is brewing in a samovar.

The poetry is mythic, thrilling, larger than life. It speaks equally to the glory and the utter humility of humanity. It extols peace and condemns militarism. The crowd cheers and swoons.

Emil wonders if he is the only one in the room who considers it bombastic and grandiose. But he is no fan of Wagner, either.

I write from pictures, from old newspaper articles and newsreels, from family stories told many times or just once, from snatches of memory, from dreams. I read about the period and places where the story is set incessantly. Then I make up stories that could have happened.

I write from pictures, from old newspaper articles and newsreels, from family stories told many times or just once, from snatches of memory, from dreams. I read about the period and places where the story is set incessantly. Then I make up stories that could have happened.

the story: my mother and father, called Gisi and Max, my father’s sister, Ida, who’s Anna in the book, and a friend of the family, whom I call Emil. Six more characters play secondary roles. None of these are entirely fictional, but what they do in the novel is certainly not what they did in life. It’s fiction.

the story: my mother and father, called Gisi and Max, my father’s sister, Ida, who’s Anna in the book, and a friend of the family, whom I call Emil. Six more characters play secondary roles. None of these are entirely fictional, but what they do in the novel is certainly not what they did in life. It’s fiction.

This morning, the morning following the Paris attacks, the dawn of the apocalypse, I came across an old, handmade book hidden among some papers I was sorting for our coming move. It is a poem by

This morning, the morning following the Paris attacks, the dawn of the apocalypse, I came across an old, handmade book hidden among some papers I was sorting for our coming move. It is a poem by

Here they are relaxing at a cabin in the Catskills right after the Second World War.

Here they are relaxing at a cabin in the Catskills right after the Second World War.