My parents were immigrants. They left Vienna in March, 1938, and arrived in Philadelphia in November, 1942, on a Portuguese ship called the Serpa Pinto.

Mes parents étaient des immigrants. Ils ont quitté Vienne en mars 1938 et sont arrivés à Philadelphie en novembre 1942, à bord d’un navire portugais appelé le Serpa Pinto.

Connected to the Quaker community through their pacifism, they settled in Philadelphia.

Liés à la communauté Quaker par leur pacifisme, ils s’installèrent à Philadelphie.

Though they’d only brought two suitcases with them in 1942, by the mid-1950’s, they’d already sold our rowhouse in a working-class suburb south of the city and built a split-level on a one acre plot in a middle-class suburb in the northwest. My little family truly lived the American dream.

Alors qu’ils n’avaient emporté que deux valises avec eux en 1942, au milieu des années 1950, ils avaient déjà vendu notre maison mitoyenne dans une banlieue ouvrière au sud de la ville et construit une maison à deux niveaux sur un terrain d’un acre dans une banlieue bourgeoise au nord-ouest. Ma petite famille vivait véritablement le rêve américain.

Occasionally, we’d have guests from Europe or other parts of the country, usually other immigrants. After a day in Philadelphia seeing the Liberty Bell, which you could touch then, and Independence Hall, we’d cram into our car, me in the middle of the front seat, guests in the back, and take route 1, or later the turnpike, through New Jersey to New York City, where my father’s sister and most of their social circle had settled.

De temps en temps, nous recevions des invités venus d’Europe ou d’autres régions du pays, généralement d’autres immigrants. Après une journée passée à Philadelphie à visiter la Liberty Bell, que l’on pouvait alors toucher, et l’Independence Hall, nous nous entassions dans notre voiture, moi au milieu du siège avant, les invités à l’arrière, et empruntions la route 1, puis l’autoroute, pour traverser le New Jersey jusqu’à New York, où la sœur de mon père et la plupart de leur cercle social s’étaient installés.

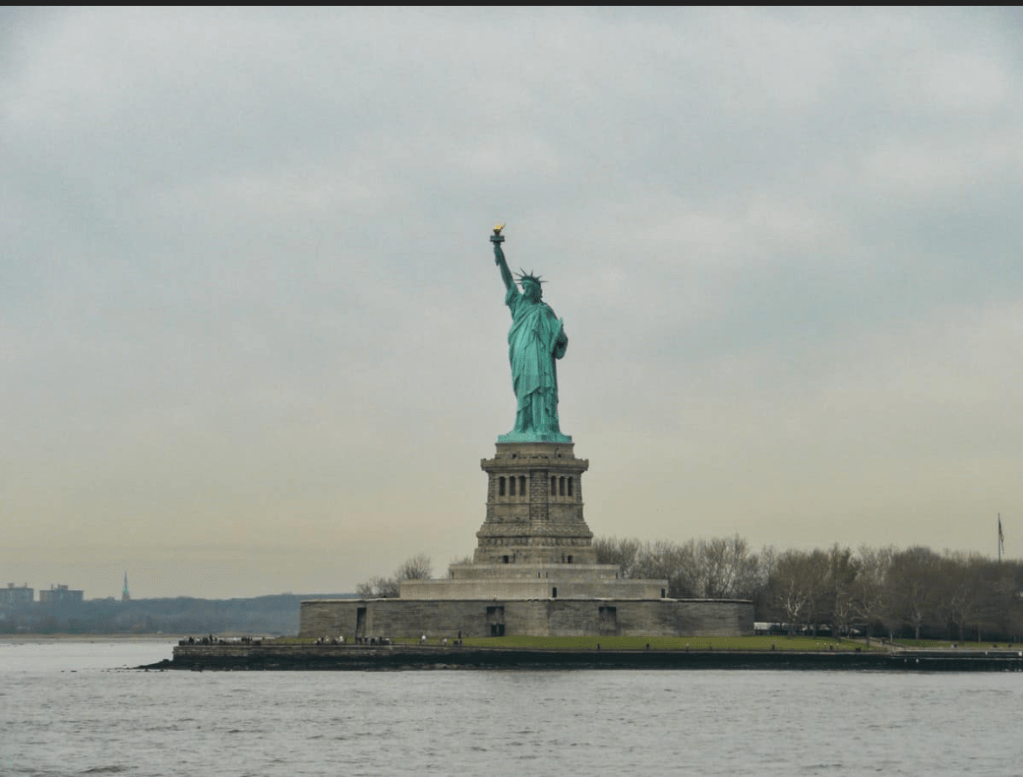

Aside from the visit to Eclair Bakery, the best part of the trip to New York was the ride on the Staten Island Ferry. It cost a quarter round-trip and it went by the Statue of Liberty.

Outre la visite à la boulangerie Eclair, le meilleur moment de notre séjour à New York a été la traversée en ferry de Staten Island. Le billet aller-retour coûtait 25 cents et nous sommes passés devant la Statue de la Liberté.

Most of the other passengers on the ferry were commuters, so it wasn’t too hard to find places to stand on the side where you could see the statue. Every time we passed her, my father would proudly tell the story of how the statue was a gift from France, where he and my mother lived between 1938 and their arrival in America. My favorite part of the tale was where the money came from to build the enormous statue and the pedestal to hold it.

La plupart des autres passagers du ferry étaient des navetteurs, il n’était donc pas trop difficile de trouver des places où se tenir debout sur le côté d’où l’on pouvait voir la statue. Chaque fois que nous passions devant elle, mon père racontait fièrement comment cette statue avait été offerte par la France, où lui et ma mère avaient vécu entre 1938 et leur arrivée en Amérique. Ce que je préférais dans cette histoire, c’était l’origine des fonds qui avaient permis de construire cette statue gigantesque et le piédestal qui la soutenait.

It wasn’t France’s national government that paid for the gift. That would have been considered inappropriate. Instead, hundreds of municipalities, from tiny villages to great cities, gave thousands of francs to build the statue. Schoolchildren saved up and donated centimes. Descendants of French soldiers who fought in the American Revolution contributed. The skin of the statue is made of copper offered by a French copper company.

Ce n’est pas le gouvernement français qui a financé ce cadeau. Cela aurait été considéré comme inapproprié. Ce sont plutôt des centaines de municipalités, des petits villages aux grandes villes, qui ont donné des milliers de francs pour construire la statue. Les écoliers ont économisé et donné des centimes. Les descendants des soldats français qui ont combattu pendant la Révolution américaine ont également contribué. La peau de la statue est faite de cuivre offert par une entreprise française spécialisée dans ce métal.

Yet when the gift was finally ready, it wasn’t certain that the statue would ever be erected in America, Many powerful Americans, including the New York Times, opposed it. But in the end, Joseph Pulitzer organized a campaign asking children to contribute pennies, and enough money was raised to install Lady Liberty in New York Harbor.

Cependant, lorsque le cadeau fut enfin prêt, il n’était pas certain que la statue serait un jour érigée en Amérique. De nombreux Américains influents, dont le New York Times, s’y opposaient. Mais finalement, Joseph Pulitzer organisa une campagne demandant aux enfants de donner quelques centimes, et suffisamment d’argent fut récolté pour installer Lady Liberty dans le port de New York.

I collected pennies. And I carried a carefully constructed Unicef donation box with me every Halloween. I knew about children contributing to great causes.

Je collectionnais les pièces de monnaie. Et chaque Halloween, je portais avec moi une boîte de dons pour l’Unicef soigneusement fabriquée. Je savais que les enfants pouvaient contribuer à de grandes causes.

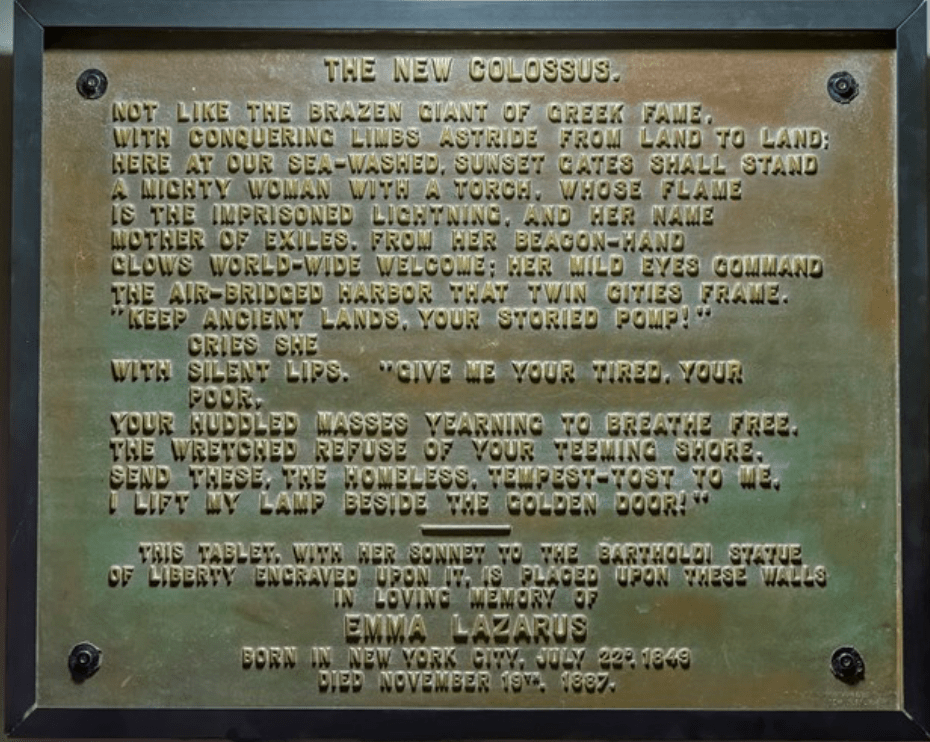

And then there was Emma Lazarus’s poem, The New Colossus, which was written for the statue.

Et puis il y avait le poème d’Emma Lazarus, The New Colossus, qui avait été écrit pour la statue.

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

« Donnez-moi vos pauvres, vos exténués,

La foule qui aspire à vivre libre,

Le rebut de vos rivages surpeuplés.

Envoyez-moi ces sans-abri, ces victimes de la tempête,

Je lève ma lampe près de la porte dorée ! »

I felt both embraced and empowered by the Statue of Liberty.

Je me suis sentie à la fois étreinte et inspirée par la Statue de la Liberté.

Now, that idealism is gone, the wretched refuse scorned, and immigrants imprisoned. The golden door is closed.

Aujourd’hui, cet idéalisme a disparu, les misérables sont méprisés et les immigrants emprisonnés. La porte dorée est fermée.

My father, a green card holder who was never naturalized, would be living in fear instead of pride.

Mon père, titulaire d’une carte verte qui n’a jamais été naturalisé, vivrait dans la peur plutôt que dans la fierté.

It breaks my heart.

Cela me brise le cœur.