To the credit of all the people who say “Can’t wait for the next volume!” on their reviews of Red Vienna, I’ve been working hard at it. Underground ends at the Anschluss, when most of Austria joyfully welcomes Hitler as their leader. which takes place from March 11th to 13th, 1938.

Here’s a taste of what I wrote today. As it seems so often, the news I read in the morning seems eerily parallel to what’s happening in my story.

Here’s a photo of the man on whom I based the character, Hugo.

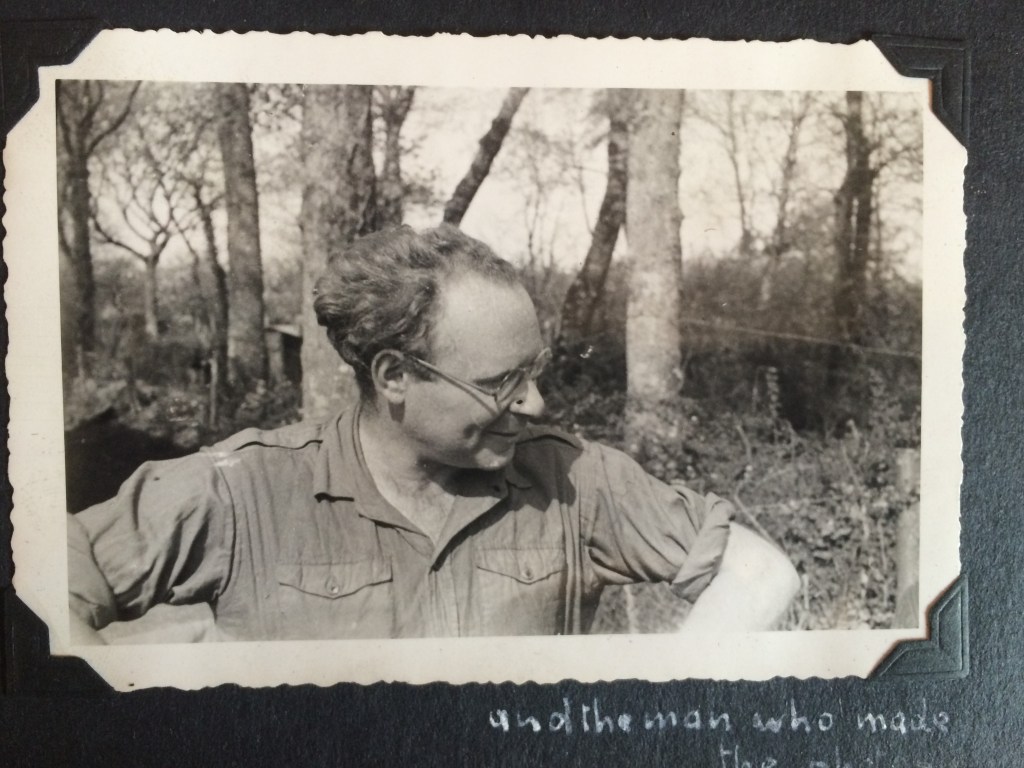

And here is my father, on whom Max is based.

January 27, 1938

Max’s workshop

Vienna

Max has the radio on whenever he can, day and night. He follows the news from as many sources as possible, hearing stories few others hear, and hearing the ones that everybody knows reported from widely varying perspectives. His shop is more popular as a source of news than it is of lamps, chairs, or radios.

“Listen to this,” he says to Hugo, who’s perched on stool at the workbench next to Max. “A German diplomat told a commentator I follow that Hitler is spending most of his time at his retreat in Berchtesgaden near the Austrian border.”

“I had heard that, yes,” says Hugo. “He’s so close he can see Austria.”

“Well, apparently he almost never goes out anymore, and here’s how he spends his time there: he has a huge collection of postcards of Vienna and other Austrian cities that he spreads out on his desk to look at while planning where to put his Brown Houses, the Nazi party headquarters. They say he spends hours at it. And he has a street map of Vienna tacked up on the wall where he’s marked the buildings he wants to replace with ones he’s designing himself. He’s obsessed—it takes up all his time.”

“Not good,” Hugo says. “Not good at all.”

“What concerns me almost as much is that I overheard someone else telling the same story to a group at the cafe yesterday and everyone thought it was funny. What do they think, that Hitler is a joke?”

“There’s no point in pretending that Hitler won’t be welcome here, Max. The Nazi tactic of causing chaos and confusion in Austria over the last few years has led most of the population to want peace at any cost, and they think becoming part of Germany will bring it.”

“It’s so ironic, isn’t it? That the man who tells the French Ambassador that he ‘will soon have Schuschnigg’s head’ should be associated with peace.” Max shakes his head. “No one believes that what I read in Feuchtwanger’s book is true either. It’s fiction, I’m told over and over, often in the most condescending way.”

“Classic it-could-never-happen-here thinking,” agrees Hugo. “Austria would never let the Jews be treated so badly. Well, we shall see soon enough.” He lights a cigarette. “I’ve finished almost all the new exit papers, by the way. Leo will be printing them in a few days.”

“That’s a relief. Are you including an Ausweis for Gisi’s mother and Gert’s parents? They would need them to get out, even if they aren’t Jewish.”

“I am, but I’m doing those last, in case I don’t have the time to finish them. Gert’s parents will never leave, and I seriously doubt Gert will. I think her family has always been more important to her than our crazy off-and-on relationship. What about Gisi?”

“She claims she’ll leave, but she started the new term at medical school this week and she told me she has some of the best professors in the program. And her mother steadfastly refuses to even consider following her. To be honest, I’m not sure if she’ll give all that up for me.”

“It’s a lot to ask. Gert would be leaving a promising career in fashion, a job she loves, and, as you saw at New Year’s, a very comfortable home that will come to her someday. What does she gain by leaving?”

Max looks pensive. “Gisi is in a similar position, minus the bourgeois apartment. What do I have to offer her? We would be leaving with not much more than the clothes on our backs.”

Hugo smiles wryly. “It sounds like you and I are talking ourselves out of leaving.”

“No, of course not. We have no choice. All Jews should be ready to go at a moment’s notice. It’s a shame so few are.”

“People don’t like to face an uncertain future. It’s so much easier to imagine that life will go on the way it is than to face the reality of a darker times ahead. I have first hand experience, though, because of Hilda and Karl’s disappearance. And I understand the pain of losing a child. I’ve already faced some of what the future could hold for many people.”

“Maybe words aren’t enough to convince people. Maybe firsthand experience is necessary. Although I have to say that for me, reading those chapters in The Oppermanns about the months that followed Hitler becoming Chancellor was enough.”

Hugo thinks for a moment. “We were fortunate to have Youth Leaders like Papanek and the others who set an example for us when they left in ’34.”

“That’s true. It’s also easier for us to imagine living somewhere else because we were raised in an Internationalist milieu. Remember? We were, what, eighteen, when we took part in the International Socialist Youth Congress? It’s very different than coming up in a Nationalist milieu that values Blood and Soil over Friendship and Peace.”

Hugo sighs deeply. “God, these are hard times.”