Here’s the chapter of Underground that I just finished. Gisi and Max are planning to write a second article with information coded in it about the safest routes for refugees to take to leave Austria if it’s necessary. It’s 1937, less than a year before the Germans will annex Austria.

Two Conversations

April 16, 1937

a cafe near Max’s shop

A couple weeks later, on that first balmy day of the year when everything blooms at once and the air is full of rich fragrance, Gisi is rushing down the city street on her way to meet Max. When she arrives at the cafe near Max’s workshop the outdoor tables are already filling with spring revelers. It had been a long, hard winter for so many, in so many ways.

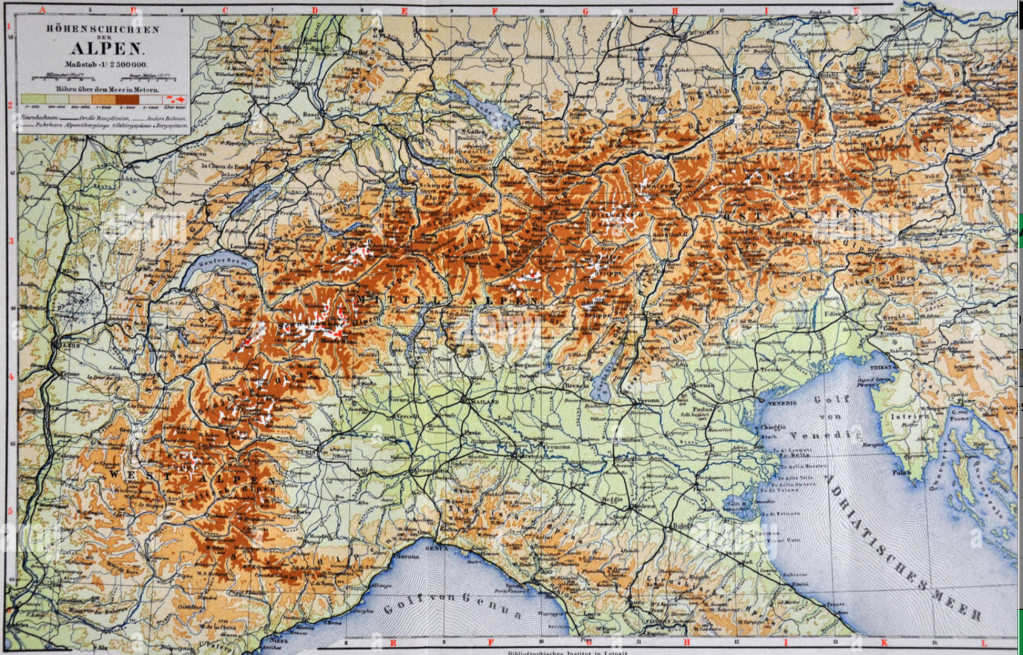

Gisi chooses an indoor table in a private corner, sits so she can watch the door, and pulls out a map from her bag. She unfolds it carefully and lays it flat on the table. Thoughtfully, she runs her finger along the routes from Austria to Italy that she and Max are considering. All of them are longer than the one they’d chosen for their first newspaper story. Even the shortest would require at least two overnight stays.

She has mixed feelings about going. Not only would all the proposed hikes take longer and require more preparation, but the story would take longer to tell and the article longer to write. And, it would take up more space in the newspaper, making it harder to sell. She sighs.

At the only other occupied table in the room, a couple in their forties is arguing. Though they’re trying to be quiet, Gisi can’t help hearing the woman’s adamant responses to her companion’s softer words.

“Don’t be a fool,” snaps the woman. “Mussolini will say whatever he wants Schuschnigg to hear.” A pause follows. “Of course he’s in league with Hitler! Why shouldn’t he be?” The pitch of her voice is rising. “Mussolini, Hitler, Franco, all the Fascists, they have nothing to lose by banding together.” Another pause. “Only we, the Jews, the immigrants, the travellers, the dark-skinned ones, all of us who are different, have something to lose!” A longer pause. Then she almost hisses, “But we have the money to get out, Fredl! And we have somewhere to go!” She listens for a moment and then says, “I don’t care if you don’t like my sister. It doesn’t matter. She’s offering to help us.” Another long pause.” And whose family has the means to do it? Yours?” She snorts.

Now Gisi can hear the man’s voice too. They’ve forgotten she’s there.

“It’s not a matter of the money, Lotte,” he says, slumping forward, elbows on the table. “You know that. You know it too well. But how can I leave my family, Lotte? What will happen to them?”

“You have a brother.”

“Yes, and you have a sister. Your sister has some good qualities and some less good ones—like my brother. No, I can’t leave. My life is built around caring for my family, and we’re rooted here. My life is in this city, in this country, no matter who is in power.”

“And my life isn’t here? You think I’m not leaving anything behind by emigrating? The issue isn’t what we have here now, Fredl. It’s what we won’t have when Germany takes over.” From the corner of her eye, Gisi sees the woman raising her hand to stop her husband from speaking. “Don’t talk about me how assimilated your family is. My cousin tells me how it is in Germany now. Jews have no rights. It doesn’t matter what kind of a Jew you are, rich or poor, practicing or not, we’re treated more and more like animals there. It’ll be the same here. Soon. Face it, Fredl. Is that what you want?”

“No. No, of course not.” He sits up and takes a sip of his coffee. “But we Viennese would never treat Jews the way the Germans have.” He puts down his cup. “We’re civilized here.” Even from across the room, Gisi can hear the doubt in his words. She realizes she hasn’t believed that for many years.

At that moment, Max enters the cafe bringing with him a rush of fresh air. He smiles at Gisi, who’s studying the map with a serious expression on her face. She looks up and smiles back at him, but the other couple’s argument is disturbing her, and her smile doesn’t reach her eyes.

He slips his jacket onto the back of the chair. “Well? Have you decided on which of the hikes we should take?”

“Oh, Max, I don’t know. Sit down and we’ll talk about them, but I have to tell you right away, I’m not sure I want to go on any of them.”

Max deflates as he sinks into his chair. “None of these particular hikes or none at all? Why not?” He can’t hide his disappointment. “I was so looking forward to it.”

Gisi lays out all her reasons: the time, the expense, the length of the article. It’s a strong argument and she becomes more convinced of it as she talks.

“So that’s it? Your mind is made up?” He stands up and begins to put on his jacket.

She relents. “I said we’d talk about the routes. You can still try to talk me into it. I just wanted you to know how I feel about it now.”

Max sits down again. “You’ve studied them? What did you find?”

“I read whatever I could find, and I talked to people. We were right about the routes we’ve been considering, but there are more. Smugglers have been using these trails for centuries. Now they’re in the business of smuggling people.”

“That makes sense,” he says. “It’s not too hard to find a smuggler to get you to Brno.”

“Although they’re not always reliable, as Hugo discovered.”

“You never know what to expect of people you meet along the way. I heard a story about a guy hiking and skiing into Switzerland who was picked up by some Heimwehr soldiers. It turned out they were more interested in what was in his rucksack than in turning him over to the authorities. Anyway, Switzerland was a kilometer away and it was many kilometers to their headquarters, so they escorted him to the border and left him there. Unfortunately, they’d robbed him, so he had nothing to show at the border, and guards turned him away. He walked back the three days it had taken him to get that far—without money, papers, skis, or even a winter coat.” Max shakes his head. “Poor guy.”

“At least he survived,” Gisi says.

“That’s true. People trying to escape from Germany wouldn’t be so lucky.”

Gisi looks down at the map. She doesn’t want to think about the horrors people are facing. “There at least a dozen well-used routes,” she says. “The shortest is the one we already tried, from Innsbruck to the Brenner Pass. Next is this one.” She points to the map. “You take the bus from Innsbruck to Naubers, which is a ski resort where strangers don’t stand out, and then it’s two and a half hours on foot to the border at Reschen Pass. It’s a much more rigorous hike than the one we took, but not as long or dangerous as most of the high mountain routes. I didn’t even study those. There are also, even at the very high altitudes, a handful of mostly flat routes that run along rivers, but they would take a very long time, days and days, even a week or more.”

“So the only reasonable one for us to explore is over the Reschen Pass. And we can do that! It’s only two and a half hours, you said?” Max is pleased.

“But they say some parts of the walk are challenging if you don’t have a head for heights. Do you have a head for heights?”

“Well…”

“And we’d need mountaineering equipment, trekking poles, warm, light-weight jackets, and better boots than either of us have.”

“Surely we can borrow what we need. Everyone in our circle supports this project.” He isn’t ready to give up.

She goes on, “It would be expensive, too. In addition to the train to Innsbruck, we’d have to pay for the bus to Naubers. Figuring out which of the hostel and restaurant owners would be willing to help refugees means we’d have to sleep and eat there, at least at some of them.”

Max has no response to that. “I don’t understand why you’re so negative about the project all of a sudden. Last time we talked about it you were all in favor. What happened?”

Gisi thinks. “I guess when I went into it more deeply, it didn’t seem so easy.”

“Nothing you’ve said has convinced me that it’s impossible though. Train, bus, and a two and a half hour trek—what’s so hard about that?”

“It’s everything together, but mostly, I find it frightening to imagine the two of us edging slowly along narrow path on a cliff with a thousand meter drop-off below us.”

“Come on, Gisi! You’ve skied so many times!”

“This is different.”

“It’s not. And everything else, we can manage easily.”

“No, Max. It would be much longer than our last trip—six hours on the train to Innsbruck and three more to Naubers, at least one night in Naubers, another six hours round-trip on foot to the border, and another night in Naubers, and then a full day to get home. And that doesn’t include all the time it’ll take to talk to people in order to write the article. Or the time it’ll take to write the article. It’s just too much.”

“So you’re giving up? You’re not interested in our project anymore?”

She sighs. “I just think it’s too much.”

He doesn’t argue. Instead, he takes his jacket and walks out the door.

At the other table, the couple who’d been arguing earlier have stopped. The wife is staring at her husband stonily as he slowly finishes his pastry.

Outdoors, clouds cover the sun and a cold wind cuts across the cafe. People are putting on their sweaters and coats.

Another gripping chapter!!!

<

div>Linda White

Sent from my iPad

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>

Thanks!

I love how two disagreements are contrasted. And then when it’s over, the weather has turned ugly. Very moving.

Thanks.

I agree Tom. The ugliness of the weather is a foreboding of what to come. Very poignant.

So good. I could really hear their voices. Visit is so so smart.

<

div dir=”ltr”>… a handful OF mostly fl

Hi Eve, I was wondering if you might like some additional proof reading assistance. I noticed a few sentences with words that seemed very likely missing. I noticed that in Red Vienna but the story was great. I would be glad to help.Kathy Bornino

Yahoo Mail: Search, Organize, Conquer